Vishnu's fifth incarnation took place in the second age, the Tretayuga. During this time the Daitya Bali, grandson of Prahlada, became king. Bali did all in his power to propitiate the gods by honouring them. He ruled well and was loved by his people, but as far as the gods were concerned his one defect was his great ambition. Having extended his kingdom as far as he could on earth, Bali could direct this ambition only in one direction towards the kingdom of the gods. The celestials consulted together and Indra was advised by the sage Brihaspati that the power Bali had gained by his sacrifices could not be resisted lndra would inevitably lose his kingdom to Bali. Brihaspati's prediction was accurate, and the gods were turned out.

The gods again consulted together and it was decided that Vishnu should become incarnate as the son of Aditi and Kasyapa, one of the seven rishis. This child grew up as the dwarf Vamana. Relying on Bali's reputation for generosity, Vamana approached the king and asked for the gift of three paces of land. The gift was no sooner granted than Vamana began to grow to enormous size. He then took two paces, which covered all the earth and the heavens and thus won back for the gods the whole of Bali's kingdom. But Bali's merits, acquired through sacrifice and austerities, had to be recognised; accordingly Vamana relinquished his right to a third pace and Bali was granted dominion over the remaining area of the universe, the nether regions, called Patala. Bali was also permitted to visit his lost kingdom once a year, and this visit is regularly celebrated in Malabar by his still devoted subjects.

Parasurama

The sixth incarnation, like the fifth, took place in the second age, the Tretayuga, at a time when the Kshatriya caste was exercising a tyranny over all others, including the Brahmins. In order to restore the power of the priestly caste, Vishnu came into the world as Parasurama, the youngest son of a strict Brahmin hermit, Jamadagni. One day Jamadagni's wife happened to see a young couple frolicking in a pool and was filled with impure thoughts. When she returned home Jamadagni divined her thoughts and was incensed, deciding that she did not deserve to live. As each of his sons returned from the forest Jamadagni bade him strike off his mother's head, but they refused and were cursed by their father to idiocy. Finally Parasurama came back from the forest, and he alone of the sons did as his father instructed and struck off his mother's head with the axe, Parasu, which was given to him by Shiva and for which he was named. Jamadagni was pleased by his son's obedience, and offered to grant him a boon. Parasurama immediately asked that his mother should be restored to life and that he himself should become invincible in single combat and enjoy long life. Both boons were granted, and life continued as before at the hermitage, with Parasurama's mother restored to purity.

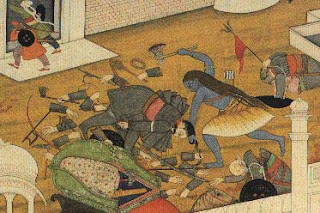

The sixth incarnation, like the fifth, took place in the second age, the Tretayuga, at a time when the Kshatriya caste was exercising a tyranny over all others, including the Brahmins. In order to restore the power of the priestly caste, Vishnu came into the world as Parasurama, the youngest son of a strict Brahmin hermit, Jamadagni. One day Jamadagni's wife happened to see a young couple frolicking in a pool and was filled with impure thoughts. When she returned home Jamadagni divined her thoughts and was incensed, deciding that she did not deserve to live. As each of his sons returned from the forest Jamadagni bade him strike off his mother's head, but they refused and were cursed by their father to idiocy. Finally Parasurama came back from the forest, and he alone of the sons did as his father instructed and struck off his mother's head with the axe, Parasu, which was given to him by Shiva and for which he was named. Jamadagni was pleased by his son's obedience, and offered to grant him a boon. Parasurama immediately asked that his mother should be restored to life and that he himself should become invincible in single combat and enjoy long life. Both boons were granted, and life continued as before at the hermitage, with Parasurama's mother restored to purity. One day, however, a powerful Kshatriya king called Kartavirya who had a thousand arms, was hunting in the forest and called at the hermitage, where he was offered hospitality by Jamadagni's wife, who was alone at the time. While a guest of the house, Kartavirya caught sight of Jamadagni's wonderful cow kamadhenu, which could grant all desires. Kartavirya decided that such a miraculous animal should be the possession of a king rather than of a hermit, so he departed, driving the cow before him, despite the helpless protests of his hostess. When Parasurama arrived home shortly thereafter and heard what had happened, he set forth immediately, overtook Kartavirya, killed him in single combat and returned with the cow.

When Kartavirya's sons heard of his death they came marching with all their troops on the hermitage. There they found the aged Jamadagni alone and killed him. When Parasurama returned to find his father dead, he vowed vengeance on the whole Kshatriya caste. His vow was accomplished in the course of twenty-one campaigns against them, in which all their men folk were exterminated, their blood filling five large lakes. Having killed all the rulers, Parasurama gave the earth into the care of the Brahmin sage Kasyapa, father of Vishnu's former avatar Vamana, father of the Adityas and of the world. Parasurama himself retired to the mountains, his main purpose achieved.

Though he was an avatar of Vishnu, he was indebted to Shiva, who had among other things given him the axe Parasu. While he was still living, another avatar of Vishnu appeared on earth and Parasurama became jealous of him. The seventh was Ramachandra, generally called Rama. Both avatars figure in the two epics, the Ramayana which celebrates Ramachandra, and the Mahabharata. In the course of the Ramayana, Parasurama is annoyed with Ramachandra for having broken the bow of Shiva, and challenges him to a trial of strength. In this Parasu-rama is defeated and consequently excluded from a seat in the celestial world. The rivalry appears also in the Mahabharata, where Parasurama, armed with Shiva's bow, is knocked senseless by Ramachandra, armed with Vishnu's. It is Parasurama who instructs Arjuna in military skills during Arjuna's twelve-year period of exile, imposed for an involuntary breach of marital propriety. Parasu-rama fights with Bhishma, the son of the goddess Ganga, whose allegiance is to Arjuna's enemies, the Kauravas; but neither of them can defeat the other, for both are protected by magic boons.

Ramachandra (Rama)

Vishnu's seventh incarnation, accomplished even while the sixth was still on earth, had as its purpose to quell the most dangerous and powerful demon king who had ever appeared. This was Ravana, ten-headed rakshasa king of Lanka (Ceylon), whose strength was overcome only after the epic struggles related in the Ramayana.

Like Hiranyaksha and Hiranyakasipu, Ravana had practised austerities in order to propitiate Brahma, who had granted him immunity from being killed by gods, Gandharvas or demons. Under the cover of this immunity and the benevolence of Shiva, whom he carefully propitiated, Ravana persecuted gods and mortals. The gods consulted on how they could be rid of Ravana, and decided that the only way was for a god to take human form, for Ravana had been too proud to ask for immunity from humans. Vishnu agreed to be that god, and all the others said they would lend their powers to humans and animals. Vishnu was accordingly born on earth to a certain king, Dasaratha, who after many years without an heir had performed the horse sacrifice. Four sons were born to him as a result. The oldest, called Rama-chandra (Rama), was born to Kausalya; the second son, Bharata, to another wife, Kaikeyi and two more sons, Lakshmana and Satrughna, to a third wife, Sumitra. Rama, whose mother had been the principal queen taking part in the sacrifice, partook of half Vishnu's nature; Bharata of a quarter; and Sumitra's sons of an eighth each. Thus the incarnation was divided among four mortals for this great task.

Rama and Lakshmana were particularly close and even as boys killed many rakshasas who were persecuting poor hermits. One day they heard that King Janaka's beautiful daughter Sita was to be married. Sita was actually an incarnation of Lakshmi, Vishnu's wife, and had received her name, meaning 'furrow', because she had been born of her own will in a field opened up by a plough. A contest was to be held and the man who could bend a bow given to Janaka by Shiva was to receive Sita's hand. Rama was the winner of this contest, actually breaking the bow.

Rama and Lakshmana were particularly close and even as boys killed many rakshasas who were persecuting poor hermits. One day they heard that King Janaka's beautiful daughter Sita was to be married. Sita was actually an incarnation of Lakshmi, Vishnu's wife, and had received her name, meaning 'furrow', because she had been born of her own will in a field opened up by a plough. A contest was to be held and the man who could bend a bow given to Janaka by Shiva was to receive Sita's hand. Rama was the winner of this contest, actually breaking the bow. Shortly after Rama's marriage to Sita, Dasaratha decided to abdicate in his favour and the coronation day was proclaimed. But meanwhile a malicious servant of Queen Kaikeyi stirred up her resentment at the pre-ferment of Rama over her own son Bharata, and during Bharata's absence from the court incited her to ask the King for a boon. Without asking what it was Dasaratha consented. He was appalled when he discovered that the boon was Bharata's succession to the throne, but he had given his word and was forced to grant it, and furthermore to send Rama into exile in the forest for fourteen years. Despite Rama's protests, Sita insisted on accompanying him, and together they set off into exile to the sounds of lamentation from the people and from Dasaratha, who died of grief within a week. Lakshmana, devoted to his brother, went with Rama and Sita. Bharata, who during all this had been away, was furious with his mother on his return, blaming her for his father's death. He spared her only out of filial duty, and went to the forest and tried to persuade Rama to return; but Rama declared that he was in honour bound to remain in exile. Bharata returned to the capital, Ayodhya, and proceeded to reign as viceroy, preserving a pair of Rama's sandals on the throne as a symbol of the rightful king.

In the forest, meanwhile, Rama and Lakshmana incurred the wrath of Ravana's sister, the rakshasi giantess Surpanakha. She first fell in love with Rama, who resisted her advances, saying that he was married, but that Lakshmana might wish to have a wife. But Lakshmana also spurned her. Suspecting that Lakshmana too was in love with Sita, Surpanakha attacked her and tried to swallow her. But Lakshmana in turn attacked the giantess, cutting off her nose, ears and breasts.

In the forest, meanwhile, Rama and Lakshmana incurred the wrath of Ravana's sister, the rakshasi giantess Surpanakha. She first fell in love with Rama, who resisted her advances, saying that he was married, but that Lakshmana might wish to have a wife. But Lakshmana also spurned her. Suspecting that Lakshmana too was in love with Sita, Surpanakha attacked her and tried to swallow her. But Lakshmana in turn attacked the giantess, cutting off her nose, ears and breasts. Surpanakha sent her younger brother Khara to avenge her. He gathered an army of fourteen thousand rakshasas and sent an advance party to attack. Rama killed these first and then destroyed Khara and his entire army. Surpanakha now sought vengeance through her older brother Ravana, but could arouse his interest only by pointing out that Sita was very beautiful and would be a fitting wife for him. Ravana accordingly set out to capture Sita by a ruse (for he knew the true identity and power' of Rama). He sent an enchanted deer to the clearing where Sita liked to pass the time. The creature was so beautiful that she wanted to possess it and asked Rama and Lakshmana to capture it for her. When the brothers had gone Ravana approached in the disguise of an ascetic and seized her. He made off with her to Lanka in his aerial chariot.

On the way Jatayu, an incarnation of Garuda, Vishnu's mount, and king of vultures, fought Ravana but was fatally wounded, living only long enough to return and tell Rama what had happened. Sita also implored the forest and the River Godavari over which she was flying to inform Rama of her fate. When they reached Lanka, Ravana tried to woo her, but she rejected all his advances. He then tried to threaten her into marriage, declaring that he would kill and eat her, but Sita was saved by the intervention of one of Ravana's wives. Ravana dared not force her because, as an inveterate wife-seducer, he was at this time doomed to die if he ever again ravished the wife of another.

Meanwhile, after a lengthy search for Sita, Rama and Lakshmana discovered Jatayu who, as he lay dying, told them the story of her disappearance. Rama piously cremated Jatayu's body, and then set about making plans to recover his wife. He made an alliance with the monkey king Sugriva, son of lndra, who had been exiled from his kingdom by his half-brother Bali (to be distinguished from the Daitya king who figured in the fifth avatar). In return for their help in regaining his kingdom, Sugriva promised to support Rama and Lakshmana against Ravana. Bali was soon killed and Sugriva restored to his throne. After some delay Sugriva raised an army of monkeys and bears, led by his general the celestial Hanuman, son of Vayu, the wind. While the army marched south towards Lanka, Hanuman, who could fly, went ahead and crossed the sea to Lanka, where he found Sita alone in a garden in Ravana's place. He told her of the plans being made for her deliverance and gave her Rama's sig-net ring as a token. Pleased with his success, Hanuman then frolicked in the enemy's garden, pulling up the plants; but he was caught by the rakshasas and brought before Ravana. Still ebullient, Hanuman raised him-self on the coiled mound of his long tail so that he was seated higher than the king. Ravana was about to kill him, but the monkey-general man-aged to stay his hand by claiming diplomatic immunity messengers from the opposing side could not be killed. Ravana nevertheless ordered the rakshasas to set fire to Hanuman's tail, by wrapping it in oily rags and lighting them. But at this moment the monkey made his escape and, trailing his burning tail and jumping from building to building, he succeeded in setting fire to the whole of Lanka.

Meanwhile, after a lengthy search for Sita, Rama and Lakshmana discovered Jatayu who, as he lay dying, told them the story of her disappearance. Rama piously cremated Jatayu's body, and then set about making plans to recover his wife. He made an alliance with the monkey king Sugriva, son of lndra, who had been exiled from his kingdom by his half-brother Bali (to be distinguished from the Daitya king who figured in the fifth avatar). In return for their help in regaining his kingdom, Sugriva promised to support Rama and Lakshmana against Ravana. Bali was soon killed and Sugriva restored to his throne. After some delay Sugriva raised an army of monkeys and bears, led by his general the celestial Hanuman, son of Vayu, the wind. While the army marched south towards Lanka, Hanuman, who could fly, went ahead and crossed the sea to Lanka, where he found Sita alone in a garden in Ravana's place. He told her of the plans being made for her deliverance and gave her Rama's sig-net ring as a token. Pleased with his success, Hanuman then frolicked in the enemy's garden, pulling up the plants; but he was caught by the rakshasas and brought before Ravana. Still ebullient, Hanuman raised him-self on the coiled mound of his long tail so that he was seated higher than the king. Ravana was about to kill him, but the monkey-general man-aged to stay his hand by claiming diplomatic immunity messengers from the opposing side could not be killed. Ravana nevertheless ordered the rakshasas to set fire to Hanuman's tail, by wrapping it in oily rags and lighting them. But at this moment the monkey made his escape and, trailing his burning tail and jumping from building to building, he succeeded in setting fire to the whole of Lanka. Hanuman flew back to the main-land and rejoined Rama, giving him valuable information about Ravana's defences. Lanka was indeed a mighty fortress, for it had originally been built by Visvakarma for the god of wealth, Kubera. The vast city, which was built mostly of gold, was surrounded by seven broad moats and seven great walls of stone and metal. It had originally formed the summit of Mount Meru which, as we shall see, was broken off by Vayu and hurled into the sea.

Shortly after Hanuman's return a bridge across the strait to Lanka was completed, despite the efforts of creatures from the dark depths of the ocean to prevent it being built. Its chief architect was a monkey leader called Nala, who was a son of Visvakarma and had the power to make stones float on water. The bridge is therefore sometimes called Nalasetu (Nala's bridge), though its usual title is Rama's Bridge.

Shortly after Hanuman's return a bridge across the strait to Lanka was completed, despite the efforts of creatures from the dark depths of the ocean to prevent it being built. Its chief architect was a monkey leader called Nala, who was a son of Visvakarma and had the power to make stones float on water. The bridge is therefore sometimes called Nalasetu (Nala's bridge), though its usual title is Rama's Bridge. A mighty battle was now fought before the gates of the city. Ravana's forces included his son Indrajit, who acquired his name and the boon of immortality from Brahma in return for the freedom of Indra, whom he had captured during Ravana's attack on Swarga, Indra's heaven, and whom he had taken prisoner to Lanka. Indrajit succeeded twice in injuring Rama and Lakshmana, but on each occasion they were cured by a magic herb which Hanuman flew all the way to the Himalayas to obtain Meanwhile Kumbhakarna, Ravana’s brother, a giant whose appetite was insatiable, was devouring hundreds of monkeys. But the monkeys were inflicting heavy losses upon the rakshasas. Finally all the rakshasa generals were killed and the battle resolved into single combat between Rama and Ravana.

As the whole company of gods looked on, these two fought a deadly battle and the earth trembled dunring the encounter. With arrows, Rama struck off Ravana's heads one after the other; but as each one fell another grew in its place. Finally Rama drew forth a magic weapon given to him by Agastya, a renowned sage and noted enemy of the rakshasas. This weapon was infused with the energy of many gods: known as the Brahma weapon, the wind was in its wings sun and fire reposed in its heads, and in its mass lay the weight of Mounts Meru and Mandara. Rama dedicated the weapon and let it loose; it flew straight to its objective in the breast of Ravana, killed him, and returned to Rama's quiver. This was the moment for great rejoicing among the gods, who showered Rama with celestial garlands and resurrected the monkeys fallen in the great battle which saw evil defeated.

Now Rama and Sita could be reunited; but to the amazement of all Rama, when he saw his wife again, spoke coldly to her; he found it hard to believe that she had been able to preserve her virtue as Ravana's captive. Sita protested her unfailing love for Rama, declared her innocence, and determined to prove it by fire-ordeal. She ordered Lakshmana to build and light a pyre and threw her-self on it; as she did so the sky pro-claimed her innocence and the fire god, Agni, led her before Rama, who now accepted her, saying that he him-self had never doubted her but had only wished for public proof.

This seemed to be a happy ending, and the monkey army returned with Rama, Lakshmana and Sita to Ayodhya, where Rama was crowned. But though Rama's reign was one of unprecedented peace and prosperity, Ravana's mischief had not yet run its course. The people of the kingdom began to murmur, doubting Sita's innocence, and though she was pregnant at the time Rama felt obliged to send her away into exile. She took refuge at Valmiki's hermitage in the forest, where she gave birth to twin sons, Kusa and Lava.

These boys, who bore the marks of their high paternity, wandered into Ayodhya when they were about fifteen years old and were recognised by their father, who thereupon sent for Sita. In order that she should publicly declare her innocence, Rama called a great assembly together. In front of it Sita called upon Earth (her mother, for she was born of a furrow) to attest to the truth of her words. Earth made a sign, but it took the form of opening in a cleft beneath Sita and swallowing her up.

These boys, who bore the marks of their high paternity, wandered into Ayodhya when they were about fifteen years old and were recognised by their father, who thereupon sent for Sita. In order that she should publicly declare her innocence, Rama called a great assembly together. In front of it Sita called upon Earth (her mother, for she was born of a furrow) to attest to the truth of her words. Earth made a sign, but it took the form of opening in a cleft beneath Sita and swallowing her up. Rama, now heartbroken, for Sita was his only wife, wished to follow her. The gods had mercy on him in his despair and sent him Time, in the guise of an ascetic, with the message that he must either stay on earth or ascend to heaven and rule over the gods. Then the sage Durvasas also came to see Rama, and demanded immediate admission to his presence, threatening dreadful curses on him if he were refused. Lakshmana, who had received Durvasas, hesitated; he knew that the interruption of a conference with Time carried the penalty of death. But preferring his own death to the curses of Durvasas on his brother, he went to fetch Rama. Then he calmly went to sit by the riverside to await death. Here the gods showered him with garlands before they conveyed him bodily to Indra's heaven. Rama's end was more deliberate; with great dignity and ceremony he walked into the River Sarayu, where Brahma's voice welcomed him from heaven and he entered into the 'glory of Vishnu'.

Krishna

Vishnu's eighth incarnation attracted to it an even greater body of mythology than the seventh, though its purpose was relatively simple: to kill Kansa, son of a demon and tyrannical king of Mathura. Of the many myths surrounding Krishna the most popular, which concern the aspects of the god in which he receives the greatest worship, have nothing to do with the reasons for his incarnation as an avatar of Vishnu. Indeed the Dionysiac myths concerning the young Krishna, with their strong Greek influence, have little to do with native ideas cur-rent during the great mythologising period of the epics. Sometimes, Krishna is considered as a great deity in his own right and then his brother Balarama is said to be Vishnu's eighth incarnation. Krishna's life falls into four main parts: childhood, when he performed great feats of strength; youth, when he dallied with the cowgirls; manhood, when he per-formed the task for which he had been born; and middle age, when he became the great ruler of Dwarka and took part in the Bharata war, acting as Arjuna's charioteer and pronouncing his great teaching on the subjects of dharma and bhakti.

Krishna's birth and childhood During the second age of the world the Yadavas of northern India, whose capital was Mathura, were ruled over by King Ugrasena. They were a peace-loving, agricultural people, who could have lived quietly had a misfortune not befallen their queen, Pavanarekha. One day as she was walking in the forest she was. waylaid and raped by the demon Drumalika, who took the shape of her husband Ugrasena. Drumalika resumed his demon form and revealed that the son to be born, Kansa, would conquer the nine divisions of the earth, be supreme ruler, and struggle with one whose name would be Krishna. Ten months later Kansa was born and as Pavanarekha remained silent about his true paternity Ugrasena assumed the son was his own. As he grew up his evil nature showed itself. He was disrespectful to his father. He murdered children, and forced the defeated King Jarasandha of Magadha to yield up two of his daughters whom he took as wives. Next he de-posed his father, ascended the throne and banned the worship of Vishnu. He extended his kingdom by conquest and committed many crimes.

Krishna's birth and childhood During the second age of the world the Yadavas of northern India, whose capital was Mathura, were ruled over by King Ugrasena. They were a peace-loving, agricultural people, who could have lived quietly had a misfortune not befallen their queen, Pavanarekha. One day as she was walking in the forest she was. waylaid and raped by the demon Drumalika, who took the shape of her husband Ugrasena. Drumalika resumed his demon form and revealed that the son to be born, Kansa, would conquer the nine divisions of the earth, be supreme ruler, and struggle with one whose name would be Krishna. Ten months later Kansa was born and as Pavanarekha remained silent about his true paternity Ugrasena assumed the son was his own. As he grew up his evil nature showed itself. He was disrespectful to his father. He murdered children, and forced the defeated King Jarasandha of Magadha to yield up two of his daughters whom he took as wives. Next he de-posed his father, ascended the throne and banned the worship of Vishnu. He extended his kingdom by conquest and committed many crimes. The gods, at the entreaty of Earth, decided it was time to intervene; Vishnu should restore the balance of good and evil. Vishnu made use of two Yadavas loyal to him. They were Devaka, an uncle of Kansa, and Vasudeva, to whom Devaka's six elder daughters were married. Vishnu ordained that the seventh daughter, Devaki, should also be married to Vasudeva. He plucked a black hair from his own body and a white one from the serpent Ananta, or Shesha, on whose coiled body he reclines, declaring that the white hair should become Devaki's seventh son, called Balarama; the black hair would be-come her eighth son, called Krishna. At Devaki's wedding, however, a voice warned Kansa of these preparations for his downfall; but he agreed to spare Devaki on condition that each of her sons should be killed at birth. Accordingly, her first six sons were slaughtered as soon as they drew breath. She then became pregnant with a seventh son, and Kansa received a second warning, for he heard that gods and goddesses were being born in the shape of cowherds. He therefore ordered the systematic killing of all the cowherds that could be found and this endangered the life of Nanda, Vasudeva's closest friend. Nevertheless it was Nanda who was chosen to help preserve Devaki's seventh and eighth sons. Vasudeva sent another of his wives, Rohini, to stay with Nanda, and Vishnu had the child in Devaki's womb transferred to that of Rohini. In due course Balarama was thus born to Rohini and Kansa was given to understand that Devaki had miscarried.

But the time came for Devaki to conceive again. Kansa took the pre-caution of imprisoning both mother and father. He had them manacled together and set men, elephants, lions and dogs to guard the prison. But the eighth child was Krishna and he re-assured his parents from the womb. Indeed when he was born all Kansa's precautions were seen to have been in vain; the manacles fell away and the baby Krishna, assuming the form of Vishnu, ordered his father to take him to the house of Nanda where Nanda's wife Yashoda had just been delivered of a child and to substitute the two babies. Krishna then resumed his infant form and Vasudeva put him in a basket, placed it on his head and left the prison freely, for the doors had swung open and the guards had fallen asleep.

But the time came for Devaki to conceive again. Kansa took the pre-caution of imprisoning both mother and father. He had them manacled together and set men, elephants, lions and dogs to guard the prison. But the eighth child was Krishna and he re-assured his parents from the womb. Indeed when he was born all Kansa's precautions were seen to have been in vain; the manacles fell away and the baby Krishna, assuming the form of Vishnu, ordered his father to take him to the house of Nanda where Nanda's wife Yashoda had just been delivered of a child and to substitute the two babies. Krishna then resumed his infant form and Vasudeva put him in a basket, placed it on his head and left the prison freely, for the doors had swung open and the guards had fallen asleep. On his way Vasudeva came to the River Jumna and attempted to ford it; but the waters rose steadily until they nearly submerged him. At this point Krishna stretched out his foot from the basket and placed it on the waters, which thereupon subsided, allowing Vasudeva to pass. At Nanda's house he found that Yashoda's baby was a girl but he took her back to the prison, whose doors reclosed and where the guards, waking up, suspected nothing. They announced the birth of a girl to Kansa, who him-self attempted to smash the infant's body on a rock. But the baby was transformed into the goddess Devi who, having told Kansa that his future enemy had escaped him and that he was powerless, herself vanished into heaven.

Nanda, who did not suspect that Krishna was not his own son, arranged a great celebration of the birth, to which he invited all the cowherds and their wives. At the festivities the Brahmins foretold that Krishna would be a slayer of demons, would bring prosperity to the land of the Yadavas and would be called Lord of the Cowgirls.

His childhood revealed his dual character. At times he seemed just an exceptionally lovable boy; in other episodes he began to show his strength and was recognised as a god.

His childhood revealed his dual character. At times he seemed just an exceptionally lovable boy; in other episodes he began to show his strength and was recognised as a god. During his first year Krishna was three times attacked by a demon. The first one was Putana, a child-killing ogress who, taking the form of a beautiful girl, was allowed to suckle Krishna. But the poison she had put on her breast could not harm Krishna who, on the contrary, sucked so hard that he drew all the life out of Putana, who resumed her monstrous form as she died. The second enemy was Saktasura, a monstrous flying demon who lighted on a cart loaded with pitchers beneath which Krishna was lying. But though the cart collapsed as Saktasura planned, it crushed him rather than Krishna, who had turned the tables with a well directed kick. The third attack was mounted by Trinavarta, a whirlwind demon who snatched Krishna out of Yashoda’s lap. A great storm arose as Trinavarta flew away with Krishna, but Krishna twisted the demon round and smashed him against a rock, at which the storm subsided.

As Krishna began to grow up he amused himself and, despite them-selves, his mother and all the womenfolk, with various pranks involving stealing the cowgirls' curds and butter, upsetting their pails of milk and blaming their children for his own mischief.

But this idyllic childhood was interrupted by the efforts of Kansa who, still searching for any child who might be the one destined to kill him, had sent demons to attack all children of Krishna's age. He overcame in turn a cow demon called Vatasura; a crane demon called Bakasura, who swallowed Krishna but was forced to release him when Krishna became too hot; and a snake demon, Ugrasura, who swallowed Krishna but whom Krishna burst open from within by expanding his own body. Again and again Krishna was attacked by Kansa's demons, but on each occasion he extricated himself, killing the ass demon Dhenuka, subduing the snake demon Kaliya by dancing on his heads, and swallowing up a fire sent to consume Krishna and his companions in a forest. Balarama, who was Krishna's constant companion, also killed some demons, such as Pralamba, a demon in human form.

But this idyllic childhood was interrupted by the efforts of Kansa who, still searching for any child who might be the one destined to kill him, had sent demons to attack all children of Krishna's age. He overcame in turn a cow demon called Vatasura; a crane demon called Bakasura, who swallowed Krishna but was forced to release him when Krishna became too hot; and a snake demon, Ugrasura, who swallowed Krishna but whom Krishna burst open from within by expanding his own body. Again and again Krishna was attacked by Kansa's demons, but on each occasion he extricated himself, killing the ass demon Dhenuka, subduing the snake demon Kaliya by dancing on his heads, and swallowing up a fire sent to consume Krishna and his companions in a forest. Balarama, who was Krishna's constant companion, also killed some demons, such as Pralamba, a demon in human form. Krishna's youth During his childhood, Krishna showed his defiance of the world of demons. During his youth he demonstrated his attitude to the Brahmins and to Indra and the Vedic gods. One day when Krishna and his companions were hungry they smelled food and found that it was being cooked by some Brahmins in preparation for a sacrifice. They asked for some to eat, but were angrily rebuffed. The Brahmins' wives, however, were eager to oblige; Krishna had a reputation as a stealer of hearts and they disobeyed their husbands and brought him food, recognizing him as God and feasting their eyes on him. When they re-turned, gratified, to their husbands they found them not only willing to forgive but angry with themselves be-cause they had missed this unexpected opportunity of serving the young god.

Krishna then persuaded Nanda and the other cowherds that their sacrifices to Indra were useless, for Indra was an inferior deity and subject to defeat by demons. Krishna convinced them that their salvation lay either in following their duty of being ruled by their fate, or in worshipping their early nature divinities, which in their case were contained in the spirit of the mountain, Govardhana, on which they grazed their flocks and which sheltered them and their beasts. The cowherds accordingly performed a great ceremony in honour of the mountain, and were rewarded for their devotions by the manifestation of Krishna himself as the spirit of Govardhana. Indra was enraged and forgetting who Krishna really was sent a terrible storm with torrents of rain to punish the cowherds. Krishna protected them from the flooding that this seven-day storm would normally have produced by raising the mountain on one finger, giving the cow-herds shelter underneath. Indra admitted his defeat. He descended to earth accompanied by his white elephant Airavata and the cow of plenty, Surabhi, and worshipped Krishna.

The story of the Brahmins' wives hints at an aspect of the Krishna myth which receives more attention than any other: his amorous adventures with women, in particular the married cowgirls (gopis). All these stories are noted for the beauty of their sensuous descriptions, but though a symbolic, spiritual meaning is ascribed to them all, it must be remarked that in later life Krishna repudiated his cowgirl loves and became the model husband and embodiment of married bliss. However, as is often said in Indian scriptures, the gods are not to be judged by human moral standards and many of the cowherds and cowgirls were, moreover, divine in-carnations on earth.

Krishna's amorous adventures began when he was young, and developed naturally from his childhood teasing of the cowgirls. One day when a group of them, already smitten with love for him, went bathing in the River Jumna in an attempt to make their wishes come true, Krishna came across them as they were calling out his name. He stole their clothes and hid with them in a tree. Despite their earlier pleas the cowgirls were mortified at the situation and tried to hide their nakedness beneath the water; but Krishna told them that Varuna inhabited the water so they were no better off in it. He insisted that each of the cowgirls come forward to the - tree to receive back her clothes. Sending them away after all this teasing, Krishna mollified them by promising that he would dance with them in the following autumn.

When autumn came, Krishna went one moonlit night into the forest and played upon his flute to call the cowgirls, who all slipped away from their husbands and went to join him. After some teasing on his part the dance began, sending the lovesick girls into ecstasies of delight, each one dancing with Krishna as if he were her lover. But Krishna slipped away with one of them and when the other girls realised they were alone they set out with lamentations to look for him. First they found his footprints, accompanied by those of a girl. But the girl, too sure of herself and proud at being singled out, had asked

When autumn came, Krishna went one moonlit night into the forest and played upon his flute to call the cowgirls, who all slipped away from their husbands and went to join him. After some teasing on his part the dance began, sending the lovesick girls into ecstasies of delight, each one dancing with Krishna as if he were her lover. But Krishna slipped away with one of them and when the other girls realised they were alone they set out with lamentations to look for him. First they found his footprints, accompanied by those of a girl. But the girl, too sure of herself and proud at being singled out, had asked Krishna to carry her; annoyed, he abandoned her on the spot. The others found her, and after their end-less search and entreaties that he should return, Krishna relented. They took up the dance again. The girls became frantic with desire and, using his powers of delusion, Krishna made each believe that he was dancing with, embracing and loving her. The dance and its erotic delights continued for six months and ended with the whole company bathing in the River Jumna. The girls returned to their homes, and found that no one or knew they had ever been away.

The story of the girl who was singled out is elaborated in Indian poetry (rather than in myth), where she is called Radha. The plight of the lovelorn girl is described as she waits for Krishna while he dallies with others, and the emotions of each of them at the various stages of their story, their misunderstandings and the fulfilment of their love, became the classical images of Indian love poetry.

The slaying of Kansa Meanwhile, the attacks of Kansa's demons continued. One of them took place at night when Krishna and Balarama were with the cowgirls. Sankhasura, a yak. sha demon, came among them and attacked some of the girls; hearing their screams, Krishna pursued Sankhasura and cut off his head. On another night, a bull demon careered among the herd, but Krishna caught it and broke its neck.

About this time Kansa was informed by a sage of the identity of his future killer and the rest of the story, He immediately cast Vasudeva and Devaki into prison and laid plans to capture Krishna. He decided that the best way would be to lure Krishna to Mathura after failing in some more attempts to kill him in the forest by sending Kesin, the same asura who had once fought and nearly overcome Indra. Kesin took the form of a horse, but again Krishna was equal to his opponent; he thrust his hand down the throat of the horse, causing it to swell within. The horse burst apart. Then Kansa sent a wolf demon to waylay Krishna. He disguised himself as a beggar; but once more Krishna was prepared, and when the demon resumed his true form and attacked him, he seized and strangled him.

Kansa now abandoned such tactics and sent the head of his court, Akrura, to invite Krishna to attend a great sacrifice at Mathura in honour of Shiva. But Akrura was a secret devotee of Krishna and warned him that Kansa had arranged for him to be killed in a match with a wrestler called Chanura, and that he had stationed at the gates a savage elephant which was to trample Krishna to death should the other plan fail.

Despite the protests of the cowgirls, Krishna, Balarama and a party of the cowherds set off for Mathura, where news of their arrival had gone before them. In Mathura the women leant from their windows and rooftops to greet Krishna; Kansa's tailor himself made them new clothes; another of his servants, the hunchback Kubja, anointed Krishna with perfume, in re-turn for which he straightened her back.

Despite the protests of the cowgirls, Krishna, Balarama and a party of the cowherds set off for Mathura, where news of their arrival had gone before them. In Mathura the women leant from their windows and rooftops to greet Krishna; Kansa's tailor himself made them new clothes; another of his servants, the hunchback Kubja, anointed Krishna with perfume, in re-turn for which he straightened her back. At the gate of the city Krishna picked up the great bow of Shiva and broke it into pieces (just as Rama had broken it) and killed all the guards. As he entered Mathura the great elephant attacked him, but after a mighty struggle was overcome. Balarama and Krishna took the tusks and paraded around with them. Then Chanura and the other wrestlers attempted to worst the brothers, but one after the other were routed. Kansa, now desperate, ordered his demons to bring forth Krishna's parents and his own father Ugrasena; they were to be put to death together with Krishna and Balarama when the brothers were overcome. When news of this reached Krishna he slew the remaining demons without mercy, then Kansa arid his eight brothers.

The main object of his life, the killing of Kansa, was now achieved but Krishna was not yet satisfied. Kansa's allies were still at large and powerful enough to disturb the balance of good and evil just as Kansa had done. Having restored Ugrasena to his rightful throne and been reunited with his real parents, Vasudeva and Devaki, Krishna himself abandoned the pastoral life and became a sort of feudal prince, thus entering the last phase of his life.

Krishna the prince Krishna was shortly justified in his decision to continue the fight against the demons, for another, a former rival of Kansa named Jarasandha, soon summoned up great armies of demons at the insistence of his two daughters, Kansa's widows. Among his many allies was another demon, Kalayavana. Seven-teen times Jarasandha and his armies attacked Mathura and were defeated by Krishna and Balarama single-handed, and each time the troops were slaughtered but Jarasandha was released to return, bringing more demon troops to be slaughtered.

Krishna the prince Krishna was shortly justified in his decision to continue the fight against the demons, for another, a former rival of Kansa named Jarasandha, soon summoned up great armies of demons at the insistence of his two daughters, Kansa's widows. Among his many allies was another demon, Kalayavana. Seven-teen times Jarasandha and his armies attacked Mathura and were defeated by Krishna and Balarama single-handed, and each time the troops were slaughtered but Jarasandha was released to return, bringing more demon troops to be slaughtered. Finally Krishna wearied of these battles and decided to build a new capital which would be easier to de-fend. He assigned to Visvakarma, the divine architect, the task of building in one night the fortress city of Dwarka (on the west coast; historically, settled by the Aryans about the sixth century B.C.). When it was completed all the Yadavas were trans-ported to the new capital; on the way the demons were allowed to believe that they had encircled them on a hill and destroyed them by fire.

Krishna was now ready to settle down and sought wives for himself and his brother. Balarama married a princess called Revati and Krishna heard of a beautiful princess called Rukmini, who was meanwhile told of Krishna by Shiva and Brahma disguised as beggars. Both fell in love at the mere description of the other, one the stage was set for a great romantic passion which was to supersede all those of Krishna's youth.

Rukmini was betrothed (on the advice of her evil brother Rukma) to Sisupala, a cousin of Krishna but an avatar of the demon whose other avatars were Hiranyakasipu and Ravana. Just before the wedding was due to take place Rukmini sent a letter to Krishna beseeching his intervention. He answered it by arriving on the wedding morning while Rukmini was praying to Devi and snatching her away in his chariot. Rukma, Sisupala and Jarasandha who was present with his demon army for the wedding decided to avenge this, but Balarama routed the demons and all but Rukma fled. He tried to kill Krishna, but was taken captive. Rukmini begged for his life and Balarama released him.

Krishna now married Rukmini and celebrated the defeat of yet more demons at the time of his nuptials. In the same way he married seven further wives; each marriage was opposed in some way by demons and so brought about the destruction of yet more evil. Thus Krishna married Jambavati, daughter of the king of the bears Jambavan, and Satyabhama. daughter of Satrajit, and Kalindi, daughter of the sun, and four other girls.

Krishna now married Rukmini and celebrated the defeat of yet more demons at the time of his nuptials. In the same way he married seven further wives; each marriage was opposed in some way by demons and so brought about the destruction of yet more evil. Thus Krishna married Jambavati, daughter of the king of the bears Jambavan, and Satyabhama. daughter of Satrajit, and Kalindi, daughter of the sun, and four other girls. He now seemed to have achieved the aims for which he was born, and Earth appealed to Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva for a reward for her part in securing the presence of Krishna in the world. She requested a son who would never die and who would never be equalled. The three gods granted her a boon but not quite in the form that she expected, for they also warned her that the son, Naraka, would be attacked by Krishna and killed by him at Earth's own request.

Naraka became the powerful king of Pragjyotisha and conquered all the kings of the earth; he became an implacable enemy of the gods in the sky and routed them; carried off the earrings of the mother of the gods Aditi, and wore them in his impregnable castle at Pragjyotisha; he took Indra's canopy and placed it over his own head; took into captivity sixteen thousand one hundred girls, earthly and divine; and finally, taking the form of an elephant, he raped the daughter of Visvakarma, the divine architect.

The gods' prophecies were duly fulfilled. Krishna attacked and defeated Naraka, though he was assisted in his defence of Pragjyotisha by the five-headed arch-demon Muru and his seven sons. When the vast demon armies had been defeated the palace was opened to reveal the countless jewels Naraka had amassed besides the earrings of Aditi, the canopy of Indra, and the-sixteen thousand one hundred virgins. Krishna took all these girls back to Dwarka and married them, for on seeing him all had fallen in love with him.

The gods' prophecies were duly fulfilled. Krishna attacked and defeated Naraka, though he was assisted in his defence of Pragjyotisha by the five-headed arch-demon Muru and his seven sons. When the vast demon armies had been defeated the palace was opened to reveal the countless jewels Naraka had amassed besides the earrings of Aditi, the canopy of Indra, and the-sixteen thousand one hundred virgins. Krishna took all these girls back to Dwarka and married them, for on seeing him all had fallen in love with him. Krishna now settled down with his sixteen thousand one hundred and eight wives and was able to delight them all simultaneously. In due course each of them bore him ten sons and one daughter, and despite the great number of his wives, he was aware of their least whim and ready to pander to their every desire. One day he gave Rukmini a flower from the Parijata or Kalpa tree, the heavenly wishing tree which grew in Indra's heaven and belonged to Indrani. A sight of this tree rejuvenated the old, and when Krishna's third wife, Satyabhama, saw the present he had made to Rukmini, she asked him to bring her the whole tree. So Krishna set off for lndra's heaven, taking with him lndra's canopy and Aditi's ear-rings, and asked for the tree. But Indra had not forgotten his humiliation over the Govardhana episode and re-fused, whereupon Krishna seized the tree and made off with it. Indra raised forces and pursued him but was defeated; however, Krishna returned the tree of his own free will a year later. The demons meanwhile were not forgotten; many of their leaders whom Krishna and Balarama had earlier defeated were plotting revenge. Jarasandha had by now imprisoned twenty thousand rajas, so Krishna set out with two of his Pan-Java cousins, Bhima and Arjuna, to release them.

The climax of Krishna's long battle with the forces of evil came, as we shall see, in the struggle between the Pandavas and the Kauravas. Throughout his career Krishna had been related by family ties to both gods and demons. So in the Mahabharata he was related to both the good Pandavas and the evil Kauravas. He took no active part in the battles, only giving advice and letting the mortal warriors fight out the epic struggle. The most important advice he gave is contained in the Bhagavad Gita, where he explained to Arjuna that all is illusion, including battle and death in arms, and that it is not the prerogative of human beings to question their duty: they must merely follow it, and leave the higher perspective to the gods. Nevertheless, through his intervention Krishna fin-ally secured that for which he came to earth even though to the human protagonists the struggle must have seemed futile.

Krishna now decided that he could return to heaven. But his own mortal end seems tragic; the weapons which were to destroy the Yadava race and bring about his own death were created as the result of a curse by some Brahmins who had been mocked by Yadava boys, one of whom, Samba, was Krishna's son by Jambavati. The Brahmins declared that Samba, who had dressed up as a pregnant woman, would give birth to an iron club that would cause the downfall of the Yadavas. In due course the club was 'born', and though it was smashed by order of King Ugrasena and thrown into the sea, splinters from it escaped destruction; one was swallowed by a fish, later found and made into an arrow head; the others grew into some rushes hard as iron.

Portents now began to appear in Dwarka of impending destruction, and the Yadavas, frightened by the storms and lightning, misshapen births and other horrors appearing all about them, asked Krishna how they might avert catastrophe. On his advice the men set out on a pilgrimage to Prabhasa. But after performing the various rituals, the Yadavas fell to drinking by the river and were assailed by a destructive flame of dissension. In the fight which ensued Krishna's intervention only made their fury greater, and by the end they had all been killed either by each other or by Krishna, who became angry with them. The weapons they used were the rushes growing by the river bank which were the very ones which grew from the splintered club.

Both Krishna and Balarama were now free to leave the earth. Balarama performed austerities by the seashore and, dying, was rejoined to the Absolute. Shesha or Ananta, the divine serpent from whose white hair Balarama was born, flowed out from his mouth. The ocean came to meet him, carrying other serpents in its waters.

Both Krishna and Balarama were now free to leave the earth. Balarama performed austerities by the seashore and, dying, was rejoined to the Absolute. Shesha or Ananta, the divine serpent from whose white hair Balarama was born, flowed out from his mouth. The ocean came to meet him, carrying other serpents in its waters. Krishna too assumed a yogic posture of abstraction. He sat beneath a fig tree with his left heel pointing out-wards. A passing hunter, his arrow tipped with the one remaining splinter of the iron club, mistook Krishna's foot for a deer and shot at it, thus piercing Krishna's one vulnerable spot and mortally wounding him. The hunter, coming closer and recognizing Krishna, immediately asked his pardon. He was forgiven and granted liberation.

Finally, before he died, Krishna sent word to Dwarka that the city would shortly be engulfed by the ocean and warned the remaining Yadavas to leave. But first a great funeral was held for Krishna and Balarama. Vasudeva, Devaki and Rohini, who died of grief at the news of Krishna's death, were placed on the funeral pyre with his body and that of Balarama; they were joined by Krishna's eight principal wives, Balarama's wives, and King Ugrasena, who threw themselves on the flames.

Buddha

Vishnu's ninth incarnation, appearing at the start of the Kaliyuga (the pre-sent age), clearly represents an attempt to subordinate Buddhism to the Hindu system, and in it the means employed to preserve the world differ radically from those in all the other avatars. Vishnu in his Buddha incarnation was not the straightforward heroic upholder of virtue, but rather the devious devil's advocate, who propagated ideas which would lead to wickedness and weaken the opponents of the gods, causing them ultimately either to be destroyed or to turn back for their salvation to their old faith in the traditional gods.

The doctrines supposedly put forward by Buddha bear only a distorted relation to Buddha's teaching as understood by his followers. He is said to have taught that the world has no creator and therefore no universal spirit of whom Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva are manifestations. The three supreme gods of the Hindus were therefore just ordinary mortal beings on a par with men. The doctrine of samsara and the associated idea that people should follow their duty dharma, as prescribed for them according to their caste had no validity; for death was no more than peaceful sleep and annihilation heaven and hell existed only on earth the one being pleasure and the other bodily suffering. Sacrifices were of no value, for the only true blessing was the individual's release from ignorance. The pursuit of pleasure was to be narrowly interpreted; to propagate this doctrine Lakshmi was incarnated as a woman who taught her disciples that since the body after death simply crumbled, heaven on earth was to be sought exclusively through sexual pleasures.

The doctrines supposedly put forward by Buddha bear only a distorted relation to Buddha's teaching as understood by his followers. He is said to have taught that the world has no creator and therefore no universal spirit of whom Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva are manifestations. The three supreme gods of the Hindus were therefore just ordinary mortal beings on a par with men. The doctrine of samsara and the associated idea that people should follow their duty dharma, as prescribed for them according to their caste had no validity; for death was no more than peaceful sleep and annihilation heaven and hell existed only on earth the one being pleasure and the other bodily suffering. Sacrifices were of no value, for the only true blessing was the individual's release from ignorance. The pursuit of pleasure was to be narrowly interpreted; to propagate this doctrine Lakshmi was incarnated as a woman who taught her disciples that since the body after death simply crumbled, heaven on earth was to be sought exclusively through sexual pleasures. Ironically, as we shall see, the Buddhists did in some sense turn to Hindu belief, though this movement was far from stemming from Buddha's hedonistic teaching rather the reverse. The mythology and cosmology that became attached to Buddhism as it became a popular mass religion, rather than a philosophers’ creed, were rooted in Hindu belief and the Hindu gods even inhabited some of the lower heavens of the Buddhist cosmos.

Kalki

The tenth and last incarnation of Vishnu has yet to come. It will usher in the end of our present age. Social and spiritual life will have degenerated to their lowest point. Sovereigns will set the tone for the final decline; they will be mean-minded and of limited power but during their short reigns they will attempt to profit to the maximum from their power. They will kill their subjects and their neighbors will follow their example, and nothing will count but outward show. Even the Brahmins will have nothing to distinguish them but their sacred thread, while the apparent wealth of the materialists will be an empty display, for real worth will have departed from everything. Truth and love will disappear from the earth, falsehood will be the common currency of social existence and sensuality the sole bond between man and wife. India will lose its sacred associations, and the earth will be worshipped for its mineral treasures alone. The sacred rites will disappear: mere washing will pass for purification; mutual assent will replace the marriage ceremony; bluff will replace learning; and the robes of office will confer the right to govern. Finally even the appearance of civilization will vanish: the people will revert to an animal existence, wearing nothing the bark of trees, feeding upon the wild fruits of the forest, and exposed the elements. No man or woman will live for longer than twenty-three years.

The tenth and last incarnation of Vishnu has yet to come. It will usher in the end of our present age. Social and spiritual life will have degenerated to their lowest point. Sovereigns will set the tone for the final decline; they will be mean-minded and of limited power but during their short reigns they will attempt to profit to the maximum from their power. They will kill their subjects and their neighbors will follow their example, and nothing will count but outward show. Even the Brahmins will have nothing to distinguish them but their sacred thread, while the apparent wealth of the materialists will be an empty display, for real worth will have departed from everything. Truth and love will disappear from the earth, falsehood will be the common currency of social existence and sensuality the sole bond between man and wife. India will lose its sacred associations, and the earth will be worshipped for its mineral treasures alone. The sacred rites will disappear: mere washing will pass for purification; mutual assent will replace the marriage ceremony; bluff will replace learning; and the robes of office will confer the right to govern. Finally even the appearance of civilization will vanish: the people will revert to an animal existence, wearing nothing the bark of trees, feeding upon the wild fruits of the forest, and exposed the elements. No man or woman will live for longer than twenty-three years. At this point of degeneration Vishnu will appear in person on earth, riding a white horse, Kalki, which is his tenth incarnation. Vishnu will ride through the world, his arm aloft and bearing a drawn sword blazing like a comet. He will accomplish the final destruction of the wicked and prepare for the renewal of creation and the resurgence of virtue in the next Mahayuga.