Just as each caste had its particular duties to follow, there is also the dharma of the four ashramas (or stages) in each of our lives.

Just as each caste had its particular duties to follow, there is also the dharma of the four ashramas (or stages) in each of our lives. Brahmachari or Student

The first stage is that of the Brahmachari or the stage of life of the student which began, in the case of the first three classes which educated their children, with the Upanayana or the thread ceremony. In ancient times girls were also given this initiation, as can be seen from temple sculptures where women also wear the sacred thread, but this was given up later on.

The three threads remind a young man of the Pranava (OM, the symbol of the Absolute), Medha (intelligence) and Shraddha (diligence), the three essential guides for education. He is taught the powerful Gayatri Mantra for the worship of the Sun so that he may absorb its brilliance and effulgence. In olden days students lived with their teacher or Guru in a gurukula (or school) usually set in the midst of a forest. The rich and the poor boy, the prince and the pauper, lived and studied together. It was a life involving service to the Guru and his family, the practice of Yoga, the study of the scriptures, the arts and the sciences, and a life of simplicity, celibacy and spartan self-discipline.

On their departure after the training was over, the Guru exhorted his pupils to speak only the truth, to work without forgetting Dharma, to serve elders, to remember the teachings of the Vedas and to regard one's mother, father, teacher and guest as divine beings to be revered and honoured.

The beauty of the life of the student in the guru kula has few parallels and the fall in the quality of education in schools and colleges today can be traced to the inadequate emphasis placed by present-day society on the totality of education and the need for it to encompass all aspects of a student's life and not book study alone. Equally serious today is the neglect of the study of our past leading to rootlessness amongst the young.

The beauty of the life of the student in the guru kula has few parallels and the fall in the quality of education in schools and colleges today can be traced to the inadequate emphasis placed by present-day society on the totality of education and the need for it to encompass all aspects of a student's life and not book study alone. Equally serious today is the neglect of the study of our past leading to rootlessness amongst the young. Also, it is essential today that we reintroduce at least a symbolic thread ceremony for all classes and sects of Hindus, for boys and girls, and through it initiate the young into their quest for knowledge.

Grihastha or Householder

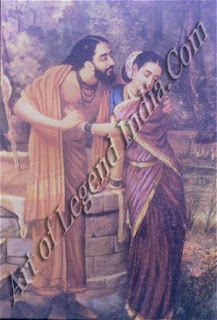

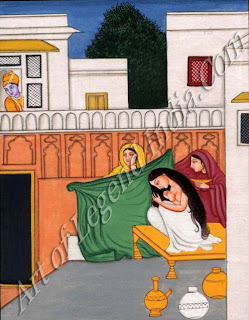

The second stage in one's life is that of the Grihastha or householder. This stage begins when the student returns from his studies, marries and takes on the duties of a householder.

The Hindu marriage is a sacred step in one's spiritual growth, and not a contract. Like Goddess Parvati, the wife is ardhangini, part of her husband. No religious ritual can be performed by a man without his wife. No man's or woman's life is believed to be complete without marriage.

The Hindu marriage is a sacred step in one's spiritual growth, and not a contract. Like Goddess Parvati, the wife is ardhangini, part of her husband. No religious ritual can be performed by a man without his wife. No man's or woman's life is believed to be complete without marriage. Every step taken in the marriage ceremony is symbolic.

The wedding ceremony takes place in front of Agni, the god of Fire. Agni personifies the power and light of the Great God. On one side of the fire is a pot of water for purification, and on the other, a flat stone.

At the start of the marriage ceremony, the father of the bride gives away his daughter, symbolic of Goddess Lakshmi, to the groom, who is deemed to be Vishnu himself. The mantra that is chanted is the same that was first recited by King Janaka while giving his daughter, Seeta, in marriage to Rama:

"This Seeta, my daughter, will be your helpmate in discharging your religious obligations. Take her hand in yours and make her your own. She will be your alter ego, ever devoted to you. She is blessed and will be as inseparable from you as is your shadow".

Then comes the panigrahana ceremony. Holding the bride's hand in his, the groom says, "I hold your hand for happiness. May we both live to a ripe old age. You are the queen and shall rule over my home. You are the Sama Veda, I am the Rig Veda", (implying that they are part of one another). "I am heaven and you are the earth. Let us marry and be joined together." The couples go around the fire and water thrice, clock-wise, while the groom says these words.

Then comes the panigrahana ceremony. Holding the bride's hand in his, the groom says, "I hold your hand for happiness. May we both live to a ripe old age. You are the queen and shall rule over my home. You are the Sama Veda, I am the Rig Veda", (implying that they are part of one another). "I am heaven and you are the earth. Let us marry and be joined together." The couples go around the fire and water thrice, clock-wise, while the groom says these words. They then touch each other's hearts while the groom says, "Your heart I take in mine. Whatever is in your heart shall be in mine whatever is in mine shall be in yours. Our hearts shall be one, our minds shall be one. May God make us one". The bride then mounts the stone, symbolic of the strength of their union.

The couple then take the saptapadi or seven steps together during which the groom prays, "With the first step for food and sustenance, with the second step for strength, with the third step for keeping ours vows and ideals, with the fourth step for a comfortable life, with the fifth step for the welfare of our cattle, with the sixth step for our life together through all the seasons, and with the seventh step for fulfilling our religious duties". Walking hand in hand, taking seven steps together is symbolic of their lives together as man and wife and, equally, as close friends.

The bride prays to Agni, the god of Fire, to witness the marriage, for the prosperity of her new home. Water is sipped by the couple to wash away impurities and to start a new life.

On the wedding night, the groom is shown Dhruva (the Pole Star), and asked to be as unmoving and constant in his love and devotion as the child Dhruva was to Vishnu (for which he was turned into the unmoving Pole Star after death). The bride is shown the stars, Vasishta and Arundati (part of the Great Bear constellation, known as the Sapta Rishis or seven sages in Indian astronomy), symbolic of a devoted couple who are never separated and are always seen together in the skies.

All other customs, such as tying the man galasutra or thali, putting sindoor on the parting, and exchanging garlands are purely local social customs and not instrinsic or essential to the marriage ceremony. The existence of agni (fire) and taking the seven steps are basic essentials of a Hindu wedding. The marriage ceremony, if performed with faith, is considered of great spiritual merit to the parents of the bride who give away their precious daughter.

The word `vivaha' meaning marriage also means that which sustains Dharma or righteousness. It is realised that to make a marriage successful is difficult and requires great sacrifices and adjustability which also help develop character. It is the householder who practises right conduct (Dharma), earns material wealth (Artha), permits himself a life of love and passion (Kama) with his wife and attains salvation (Moksha).

The word `vivaha' meaning marriage also means that which sustains Dharma or righteousness. It is realised that to make a marriage successful is difficult and requires great sacrifices and adjustability which also help develop character. It is the householder who practises right conduct (Dharma), earns material wealth (Artha), permits himself a life of love and passion (Kama) with his wife and attains salvation (Moksha). Therefore the second stage, the ashrama of the Grihastha, is considered the most important of the four. The householder is expected to earn a living with integrity and by honest means and to give away one-tenth of what he earns in charity.

He is expected to give happiness and joy to his wife by providing her with a good home. It is obligatory for him to look after his children, educate and marry them.

He is expected to give happiness and joy to his wife by providing her with a good home. It is obligatory for him to look after his children, educate and marry them. Charity is essential in a married couple's life. Food is to be given to crows and birds, to cattle and other animals everyday. Hospitality and providing for one's guests are the main duties of a married couple who should not eat their main meal for the day without feeding a guest, a visitor, a relative or a poor man.

The Grihastha's life is full of social and spiritual obligations which challenge his capabilities to the hilt and try him sorely. His trials and tribulations in this period, if faced without deviation from Dharma, enable him to evolve into a superior human being with harmony as the key-note of his success.

Vanaprastha

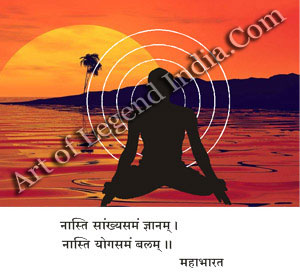

Once one's grown-up children are settled and they are able to run their own lives and look after their young children, it is time for middle-aged couple to enter the third stage and to become Vanaprasthas or, literally, those who retire to the forest. In modern parlance this means that the time has come to detach oneself from the jungle of wordly desires and attachments, concentrate on philosophical study and retire to the sylvan peace of contemplation, meditation and spiritual pursuits.

Unfortunately, in today's world, few give up their wordly desires at any stage of their lives, so even the third stage is rarely reached as most people are still involved in the rat-race of making money and acquiring more and more consumer goods, each bigger and better than one's neighbour's.

Unfortunately, in today's world, few give up their wordly desires at any stage of their lives, so even the third stage is rarely reached as most people are still involved in the rat-race of making money and acquiring more and more consumer goods, each bigger and better than one's neighbour's. At no time in the history of our land has this acquisitiveness reached the stage we are in today. Acquiring money by any means, fair or foul, aspiring for high positions, using money to gain political power, judging a man by his financial status in life, are some of the depths to which the Vanaprastha of today has fallen. These in turn have led to a widespread fall in values away from the Hindu ideal where the one most revered was not the king (with the wealth of the nation at his command) not the shopkeeper or merchant, but the mendicant and Sanyasi, who begged for alms even to feed himself.

Sanyasi

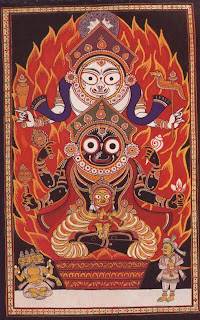

Out of those few who reach the Vanaprastha ashrama, barely a handful reach the fourth stage of the Sanyasa ashrama. One whostakes to Sanyasa gives up all wants, has no needs, does not accept money, and renounces the world. He lives on alms or the fruits of the forest and spends his time in meditation. He is beyond the rules and regulations of ordinary living and is a jivanmukta, or one liberated from ordinary life. Unfortunately visitors to our country think that all orange clad men (called sadhus or peaceful men) are holy men or Sanyasis. A few are, but the majorities are the "drop-outs" of Hindu society, often preying on the gullible.

Writer – Shakunthala Jagannathan

+c.+1503-05.jpg)

,+Late+19th+early+20th+Century,+Dhodeydrag+Gonpa,+Thimphu,+Bhutan.jpg)