Lanka Restored

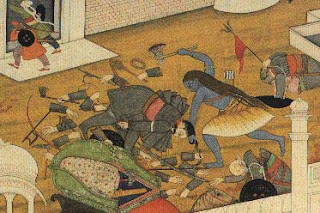

The battle was over. Ravana's huge body lay sprawled on the ground, covered in blood and surrounded by the gruesome aftermath of war, charred and mutilated remains covering the field as far as the eye could see. At his side knelt Vibhisana, with Rama standing behind him.

'O great hero,' mourned Vibhisana, 'why are you lying here, my brother, rather than on the sumptuous bed that you are used to? You did not take my advice. Now that you have fallen, the city of Lanka and all her people are reduced to ruin.'

'Do not lament,' said Rama. 'He terrorized the universe, even Indra himself. Sooner or later he had to die, and he chose to die the glorious death of a. warrior.'

'He was generous to his friends and ruthless to his enemies,' said Vibhisana, 'and religious according to his own tradition he chanted the Vedic hymns and kept a sacred fire burning in his home.'

'Now you must consider how to perform his funeral rites,' said Rama.

'He was my older brother, but he was also my enemy and lost my respect. He was cruel and deceitful, and violated other mens' wives. I do not know if he deserves a proper cremation,' confessed Vibhisana.

'He was immoral and untruthful, after the nature of a rakshasa,' replied Rama, 'but he was gifted and brave. Cremate him with respect and let enmity end with death.'

Then came Ravana's wives, braving the horrors of the battlefield to be at their husband's side. They threw themselves around him, sobbing and stroking his head.

'If only you had heeded Vibhisana and returned Sita to Rama,' they cried, 'none of this would have happened and we would be spared the curse of becoming widows.'

How could you, who conquered heaven, be overcome by a man wandering in the forest?' spoke Mandodari, Ravana's chief queen. 'The only explanation is that Vishnu, the Great Spirit and eternal sustainer of the worlds, took human form as Rama to finish your life. Sita was the cause of your downfall. The moment you touched her your end was assured. The only reason the gods did not strike you down was because they feared you, but your actions still brought the fruits they deserved. One who does good gains happiness and the sinner reaps misery; no one can escape this law. ,

'You were advised by me, Maricha, Vibhisana, your brother Kumbhakarna, and my father, but you ignored us all.' Mandodari wept on Ravana's breast and her fellow wives tried to console her.

Meanwhile Rama sent Vibhisana into the ruined city of Lanka to make the funeral arrangements and perform the closing rites for Ravana's sacred fire. Soon he returned with the sacred embers, articles of worship and firewood for the pyre carried by rakshasa priests and attendants. They decorated Ravana's linen shroud with flowers and carried his body in procession to the beach, preceded by the sacred fires and followed by weeping rakshasa women.

Vibhisana ignited the pyre while the remaining family members threw rice grains into the flames. Vedic hymns were intoned as the mourners looked on in silence.

When all was finished they returned to the city. His anger exhausted, Rama put away his weapons. A deep joy welled in his heart and his gentle demeanor returned.

Sita's Ordeal by Fire

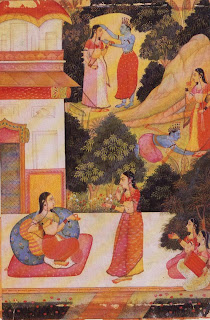

![Swearing her faithfulness to Rama, Sita decides to enter fire rather than bear his insults. The Fire god, knowing her to be pure, saves her from harm. Swearing her faithfulness to Rama, Sita decides to enter fire rather than bear his insults. The Fire god, knowing her to be pure, saves her from harm.]() With Ravana out of the way, Rama's thoughts turned to Sita. He called Hanuman and asked him to take her the news of Ravana's death. He came to the ashok grove and found her as before, unwashed and uncared for with tears in her eyes, seated on the ground beneath the tree guarded by demon women. He stood respectfully at a distance to deliver his message.

With Ravana out of the way, Rama's thoughts turned to Sita. He called Hanuman and asked him to take her the news of Ravana's death. He came to the ashok grove and found her as before, unwashed and uncared for with tears in her eyes, seated on the ground beneath the tree guarded by demon women. He stood respectfully at a distance to deliver his message.

'Lord Rama is safe and well, and has killed Ravana. He sends you this message: "After many sleepless months I have bridged the sea and fulfilled my vow to win you back. You now need have no fear as you are in the hands of Vibhisana, the new king of Lanka, who will soon come to see you". Sita was speechless with joy to hear this news and waited for more. But Hanuman remained silent.

'This news is more valuable than all the gold and jewels in the universe,' she laughed, 'and you have delivered it in such sweet words. I cannot repay you enough.'

'If you will permit me, I can deal swiftly with these cruel rakshasa women,' offered Hanuman, eager to be of service. 'They have so mistreated you. Let me kill them now with my bare hands.'

'You must not be angry with them,' reproved Sita. 'They have only done what they were ordered to do. Whatever I have suffered is due to my own sins, not to them. When others mistreat me, I will not mistreat them in return. I will show compassion to all, even if they are unrepentant murderers.' Hanuman checked himself.

'Then have you any message for your husband?' he asked.

'Tell him I long to see him!'

'You shall see him this very day.' With these words Hanuman swiftly flew back to Rama with Sita's message, and urged him to go to her at once to end her misery. Rama sighed deeply in an effort to hold back his tears. After a moment he turned to Vibhisana.

'Go quickly and fetch Sita. Before bringing her here see that she is bathed, dressed in fresh clothes, and adorned as befits a queen.'

Sita waited in the grove, expecting Rama, but instead she saw the ladies of Vibhisana's household who came to bring her to his house, where Vibhisana told her to bathe and dress in preparation for meeting Rama.

'I want to see my husband now, as I am,' she protested, but Vibhisana prevailed on her to do Rama's bidding. The ladies helped her bathe and combed out her tangled hair, dressed her in fine clothes and ornaments and placed her inside a palanquin, covered so that no one could see her. Soon she was brought by a company of rakshasas to Rama's presence.'

During this time Rama remained deep in thought, considering how to welcome Sita. The strict codes of the royal house of Iksvaku demanded that a princess violated by an . enemy must be rejected by her husband. Sita had been Ravana's prisoner for eleven months. Who knows what that immoral demon might have subjected her to? Rama trusted Sita completely, but he was determined that she must be publicly exonerated from any impropriety. He knew what he must do.

What happened next is painful to recount.

Monkeys and rakshasas crowded forward on all sides, anxious for a glimpse of the fabled princess. Vibhisana, hoping to protect Sita from the public, told her to wait in her palanquin, but Rama wanted her brought out in the open.

'These are my people and they want to see her,' he spoke sternly. 'At a time like this there are no secrets, even for royal princesses. Bring her here in front of everyone.'

Vibhisana was uncomfortable with this order, but dared not contradict him. Sita had to suffer the indignity of walking in front of thousands of curious eyes on her way to Rama. She reached him and stood at a respectful distance, her head bowed, and shyly looked into his face. As she gazed into his eyes her discomfort was forgotten for the moment and she glowed with happiness.

'I have won you back according to my vow,' announced Rama. 'The insult against me has been avenged, and its perpetrator repaid for his terrible offence against you. I am once more my own master. All this has been done with the help of Hanuman, Sugriva and Vibhisana, to whom I am indebted.'

Rama spoke without emotion, but his voice sounded strange as it rang out across the crowd. His heart bled for Sita, but he must not show it. She looked upon her lord, with tears falling down her cheeks, and dreaded what he might say next.

'I have redeemed my honour and won you back,' he went on, 'but I did not do this for your sake, fair princess, I did it for the sake of my honour and for the good name of the royal house of Iksvaku. Your honour is not so easy to redeem, since you have lived in the house of a demon who has embraced you in his arms and made you the object of his lust. You are "so desirable, Ravana could not have resisted you for long. I therefore relinquish my attachment to you. You are free to go wherever you please. If you like you can go with Lakshmana, or Bharata, or even Sugriva or the rakshasa Vibhisana. Do as you please.'

A shocked silence fell over the assembly. Sita tried to rake in what she had just heard. She had never in her life received a cross word from her husband. Now he had condemned her in public with these awful words. For her this was worse than death. She bowed her head in shame before this crowd of strangers and cried uncontrollably as Rama waited in stern silence for her response. After a little while she wiped her eyes and stood straight, her face pale and her voice trembling.

'You speak hurtful words, my lord, as if I were a common prostitute, but I am not what you take me for. I am daughter of the earth, who was seized against my will by force. If you were to reject me it would have been better if you had told me through Hanuman when he first came. Then I would have put an end to my life and saved you the trouble of coming here to kill Ravana, endangering the lives of all these innocent people. You forget that when I was a child you took my hand and promised me your protection and that I have served you faithfully ever since. My heart has always remained fixed on you, but now you of all people do not trust me. What am I to do?' Sita's voice broke with emotion. She turned to speak to Lakshmana.

'I have no desire to live when I have been falsely accused and publicly rejected by my husband. Death is my only course. Prepare a pyre for me I will enter the flames.'

Stunned at this request, Lakshmana looked at his brother. Rama nodded his assent. No one dared to contradict him, whose anger seemed capable of destroying the universe. Lakshmana mechanically went about his brother's bidding, and before long a funeral pyre had been built and set alight. The fire began to crackle. Sita circled around Rama in respect and proceeded towards the pyre. Standing before the blazing flames she called in a loud voice:

'May all the gods be my witness. I have never been unfaithful to Rama in thought, word or deed. If the Fire god knows me to be innocent, let him protect me from these flames.' Then she walked into the fire. As she entered the flames the crowd gasped in horror. The flames leapt high and parted over her head as she stepped among them, swallowing her golden form. For a moment she could be seen standing in the midst of the flames like a dazzling flame of gold, then she was lost to sight. Women screamed and fainted. A great cry, strange and terrible to hear, went up from all the monkeys; bears and rakshasas present. Rama sat immobile like one who has lost his life, and tears flooded his eyes.

As the incarnation of Vishnu, Rama had accomplished all the gods had asked of him. But the gods heard Sita's cry for help and were troubled at her ordeal. It was time for them to intervene. The creator Brahma, Shiva the destroyer, Indra the king of heaven, and others all boarded their aerial cars and flew down to earth, where they appeared shining in front of Rama and spoke to him.

'Have you forgotten who you are and who Sita is? You are the source of creation, the beginning, middle and end of all that exists. And yet you treat Sita as an ordinary fallen woman.'

'I am a human being. My name is Rama, son of Dasaratha, and Sita is my human wife. Who do you say I am?'

'You are the supreme Lord Vishnu and Sita is your eternal consort, the goddess Lakshmi,' declared Brahma. 'You are Krishna. You are the Cosmic Person, the source of all, creator of Indra and the gods, and the support of the entire creation. No one knows your origin or who you are, yet you know all living beings. You are worshipped in the form of the Vedic hymns and the mystic syllable om, and night and day are the opening and closing of your eyes.

'At our request you took human form to put an end to Ravana. Now you have accomplished this, and your devotees who praise you will be blessed for evermore.'

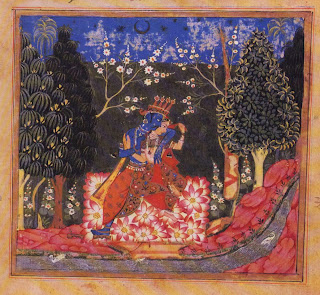

Then the Fire god, Agni, rose up out of the flames of the funeral pyre bearing Sita in his arms. She was unharmed by the fire and her clothes and ornaments, even the flowers decorating her hair, were exactly as before. Agni brought her to Rama.

'Here is your wife Sita who is without sin. She has never been unfaithful to you, in thought, word or deed. I command you to treat her gently.'

'This ordeal for Sita was necessary,' Rama explained, 'I had to absolve her from any blame and to preserve the good name of the Iksvaku race. I know she has always been faithful, but I had to prove her innocence. In truth I could not be separated from Sita any more than the sun can part from its own rays. But I thank you and accept, without reservation, your words of advice.' With these words, Sita and Rama were re-united. Then there was a further surprise.

'You have rid the world of the curse' of Ravana,' said Lord Shiva. 'Now you have one thing more to do before you return to heaven. You must bring comfort to your mother and brothers and prosperity to Ayodhya. Greet your deceased father, whom I have brought from heaven to see you.'

Rama and Lakshmana bowed in wonder as Dasaratha descended in their midst, his celestial form shining. Reaching the ground he took them in his arms.

'I am so pleased for you, dear boy,' he said to Rama, 'and at what you have achieved. You have set my mind at rest, which has long been haunted by Kaikeyi's words, and you have redeemed my soul. I now recognize you to be the Supreme Person in the guise of my son. Now you have completed fourteen years in exile, please return to Ayodhya and take up the throne.'

Turning to Lakshmana, he said, 'Your service to Rama and Sita has brought Rama success, the world happiness, and will bring you its own reward. I am deeply pleased with you, my son.' Then he spoke to Sita.

'My daughter, please forgive Rama, who was inspired only by the highest motive. You have shown your purity and courage by entering the flames, and you will be revered henceforth as unequalled among chaste women.' With those words, Dasaratha ascended, to heaven. It now remained for Indra to grant Rama one last wish.

'We are all pleased with your actions, Rama, and would like to grant you a boon. What is your wish?'

Rama was unhesitating. 'May all these monkeys and bears, who have sacrificed their lives for me, be brought back to life and returned to their wives and families.'

'It shall be done,' declared Indra. Then the monkeys and bears rose up, their limbs restored and their injuries healed, as if from a long and peaceful sleep. 'You may return to your homes,' pronounced the assembled gods. 'And Rama — be kind to the noble princess Sita. Make haste to Ayodhya, where your brother Bharata awaits you.' Then they boarded their golden aerial cars and departed for the heavens.

Homecoming

Vibhisana invited Rama to take his bath and put on royal robes and ornaments.

'I cannot bathe until I have been reunited with Bharata,' said Rama. 'For the last fourteen years he has lived as an ascetic for my sake. Now I must hurry to him. If you would please me, help me to get to Ayodhya as soon as possible.'

'That is easily done,' replied Vibhisana. 'The fabulous Puspaka airplane will fly you there by sunset. But first remain here a while and let me entertain you and your army.'

'I would not refuse you, Vibhisana, after you have done so much for me, but I long to see Bharata and my mother.'

Vibhisana summoned the airplane which arrived instantly, gleaming with its golden domes. Rama took the shy Sita in his arms and boarded the plane with Lakshmana.

'Settle peacefully in your kingdoms,' he told Sugriva, Vibhisana and their ministers. 'You have both served me well. I must return.' But they were not ready to part.

'Let us come to Ayodhya and see you crowned,' they protested. 'Only then will we return to our homes.' Rama happily agreed and invited them aboard with all their followers. Miraculously there was enough room aboard the airplane for everyone. When all was ready, the Puspaka ascended effortlessly into the sky amid great excitement. Rama took Sita to a balcony and they looked down at the island of Lanka.

'See, princess, the city of Lanka and outside it the bloody field of battle. Here, at Setubandha, is where we built the bridge across the sea and I received the blessings of Lord Shiva. Now you see Kiskindha, Sugriva's capital where I killed Vali.' As they approached Kiskindha, Sita made a request.

'Let me invite the wives of the monkeys to come with us to Ayodhya.' It was done. The airplane touched down and took aboard thousands before proceeding on its way.

'Now see Mount Rishyamukha, where I spent the rainy season in sorrow and where we first met Hanuman and Sugriva. And here is that enchanting place where we lived in our cottage and where you were carried away by Ravana, and over there is the place where the brave Jatayu died. Here are the ashrams of Agastya, Sutikishna and Sarabanga, and here is where you met the noble Anasuya, wife of Atri. Here is Chitrakoot, the most beautiful of hills, where Bharata found us.'

They stopped overnight at Bharadvaja's ashram and Rama sent Hanuman ahead with messages for Bharata. He was worried that Bharata might resent having to give up the kingdom to his brother. He need not have feared. Hanuman arrived at the village of Nandigram, outside Ayodhya, and found Bharata living as Rama had lived during his exile, dressed in deerskin, with Rama's wooden shoes occupying the central position in his court. When he heard of Rama's return he jumped for joy and hugged Hanuman, showering him with gifts.

The next morning Bharata led everyone out to meet Rama, with Rama's sandals at the head of the procession. A great cry went up when the people saw Lord Rama seated in the Puspaka airplane as it slowly descended. Rama came forward and took Bharata in his arms. Bharata hugged Lakshmana and greeted Sita, then he embraced one by one all the leading monkeys. Rama tearfully clasped the feet of his mother and offered his respects to the sage Vasistha. Bharata then placed his shoes back on his feet.

'I return to you your kingdom which I have held in trust for you,' said Bharata with emotion. 'By your grace all has flourished and my life is now fulfilled.' Again Rama hugged Bharata, while many of the monkeys, and even Vibhisana, shed a tear.

Rama was placed in the hands of barbers who shaved his beard and untangled his matted locks. Then he and Sita were bathed and dressed in royal finery. Sumantra brought up Rama's royal chariot and in grand procession entered Ayodhya, with Bharata at the reins and his brothers fanning him. Sugriva and the monkeys were welcomed into the heart of Ayodhya where Rama gave them the freedom of his royal palace and gardens.

For Rama's coronation, monkeys were sent by Sugriva to collect water from the four seas, east, south, west and north, and from five hundred rivers. Vasistha conducted the ceremony, bathing Rama with the sacred waters and installing Sita and Rama on the throne. Rama distributed gifts to all his people."

Sita looked kindly on Hanuman, unclasping her pearl necklace. She hesitated, looking shyly at her husband. Rama understood. 'Give it to the one who has pleased you best,' he said, and she placed it around Hanuman's neck.

During Rama's rule there was no hunger, crime or disease. People lived long, the earth was abundant, society prospered and all were dedicated to truth. For his people, Rama was everything and he ruled them for eleven thousand years.

Whoever daily hears this Ramayana, composed in ancient times by Valmiki, is freed from all sins. Those who hear without anger the tale of Rama's victory will overcome all difficulties and attain long life, and those away from home will be re-united with their loved ones. Rama is none other than the original Lord Vishnu, source of all the worlds, and Lakshmana is his eternal support.

Epilogue

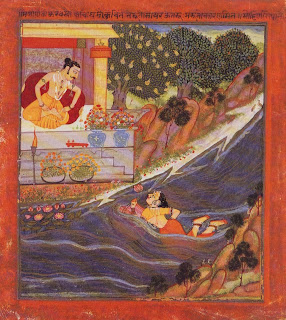

![) Sita takes refuge at the ashram of the sage Valmiki, the poet of Ramayana. ) Sita takes refuge at the ashram of the sage Valmiki, the poet of Ramayana.]() For a month after Rama's coronation, festivities and merry-making continued. When it was time for them to go, the monkeys cried and stammered; it was a sad parting. Last of all came Hanuman.

For a month after Rama's coronation, festivities and merry-making continued. When it was time for them to go, the monkeys cried and stammered; it was a sad parting. Last of all came Hanuman.

'My Lord, please grant my request,' submitted Hanuman. 'Let me always be devoted to you and no one else, and let me live as long as your story is remembered on earth.'

Rama hugged Hanuman and granted his wish, saying, 'Your fame and your life will last as long as My story is repeated, which will be until the end of the world.'

After Rama's guests had gone he spent many happy days roaming with Sita in the royal pleasure groves. In this way nearly two years passed. One day Sita appeared more beautiful than usual, and Rama knew that she was pregnant.

'My dearest Sita, you are going to have a child. Is there anything you wish?'

'I would dearly like to visit the ashrams across the Ganges, and stay one more night with those sages eating only roots and fruits.'

'Please rest tonight and tomorrow I will arrange it,' promised Rama.

That evening he sat as usual with his friends and chanced to ask them for the gossip among the people of Ayodhya concerning their king and queen.

'They praise you and your victory over Ravana,' came the reply.

'Do they say nothing against me?' Rama inquired. 'You may speak without fear.'

One of them admitted that men all over his kingdom spoke ill of his relationship with Sita. They said that since Rama had accepted Sita back after she had been touched by Ravana, they would now have to tolerate unfaithfulness from their own wives, because whatever the king does his subjects will follow. When he heard this Rama was astonished and turned to his other friends.

Is this so?' he asked in dismay.

One by one they nodded, 'It is true, my lord.' Dumbfounded and full of grief, Rama dismissed them and sat deep in thought. After a while he sent for his three brothers. They arrived to find him crying. They bowed and waited for him to speak.

'In times of trouble you three are my life,' he began. 'Now I need your help and support more than ever.' He paused while they waited anxiously.

I have just been informed that my Sita is not approved by the people they think her unchaste. This is despite the trial I subjected her to in Lanka, where the gods themselves testified to her purity. I know her to be pure, yet dishonor, for a king, is worse than any other fault. I would rather die than fail to uphold honour.

'Therefore my mind is made up. Sita has told me she wants to visit the ashrams on the other side of the Ganges. Lakshmana, tomorrow you must take her there and leave her in the care of the sage Valmiki. Please don't try to dissuade me from this.' With a heavy heart, Rama took leave of his brothers and spent the night in sorrow.

In the morning Lakshmana set off with Sita in his chariot, driven by Sumantra, on the two-day journey to the Ganges. On the way Sita noticed strange symptoms.

'How is it, Lakshmana, that my right eye throbs and my limbs shiver? My heart beats faster as though I were distressed. Is all well?'

'All is well, my lady,' Lakshmana said. But when they reached the Ganges he sat down by the river and sobbed.

'Why are you crying, Lakshmana?' asked Sita. `Do you miss Rama? Come, let us cross the Ganges now, and after one night we will return to see him.'

Lakshmana checked his tears and together they boarded a boat. Once they reached the other side and got out of the boat Lakshmana broke down.

'My heart is pierced by an arrow. I have been entrusted to carry out an awful deed for which I will be hated for ever. I would rather die!'

Sita was alarmed. 'What is it, Lakshmana? It seems you are not well, and neither was Rama when I said goodbye to him. Do tell me what is wrong.'

'Rama has heard unpleasant rumours,' Lakshmana stammered. 'It seems the people think you unchaste. In great pain he has ordered me to leave you here at Valmiki's ashram, although he knows you to be blameless. Valmiki was a close friend of our father and will care for you. Please stay here peacefully and hold Rama always in your heart.

Sita fell unconscious on the ground.

'This body of mine was created only for sorrow,' she wept. 'What sin have I com-mitted that I should be made to suffer like this? If! were not bearing Rama's child I would drown myself in the Ganges.

'Do as the king has ordered, Lakshmana,' she went on. 'Leave me here. Please wish my mother’s well, and give this message to Rama: "You know I am pure, and will always remain devoted to you. To save you from dishonor I make this sacrifice. Please treat all your citizens as you would your brothers, and bear yourself with honour, then these false rumours will be disproved. You, my husband, are dearer to me than my life." Now look at me one last time, Lakshmana, and depart.'

'I will not look at your beauty now, lady, since all my life I have looked only on your feet,' said Lakshmana through his tears. He bowed his head at her feet and boarded the boat. Without looking back he urged the boatman on.

Sita remained crying by the riverside. Her cries were heard by the young ascetics of Valmiki's ashram and they brought the news to him. He gently brought her into his ashram, reassuring her that she need have no fear. Lakshmana, from across the river, saw her taken in and returned to Ayodhya.

Valmiki knew Sita was blameless and that she carried Rama's child. He took her to the women ascetics who lived nearby as his disciples, and instructed them to care for her as their own child. There Sita lived in peace and bore twin sons named Kusa and Lava. In time, Valmiki taught them his poem describing their father's deeds, Ramayana.

With help from Lakshmana, Rama learned to live with his sorrow after the loss of Sita, and found consolation in caring for his people. But he kept her always in his heart. Twelve years passed and Ayodhya prospered. To ensure the continued well-being of the kingdom, Rama decided to perform the exalted asvamedha ceremony, as had his father before his birth. When all was ready, the sage Valmiki arrived with Kusa and Lava and told them to recite Ramayana as he had taught them.

Kusa and Lava were asked to sing their tale for the king, and all present noticed their striking resemblance to Rama. After several days of recital the story revealed them to be the sons of Sita. When Rama understood this his heart troubled him. He sent word to Valmiki inviting him to bring Sita to Ayodhya, if she so agreed, to declare her chastity and exonerate her name.

Valmiki gave his approval and brought Sita to a great gathering in the presence of Rama. He stood in front of the people and spoke.

'Your majesty, Sita has lived under my care since you abandoned her. Now she has come to proclaim her honour. I, Valmiki, who never spoke a lie, declare these twin sons of hers to be your sons and Sita to be without sin.'

'Honorable sage,' said Rama, 'I have always known that Sita is pure and I acknowledge these two boys as my sons. The gods themselves vouched for Sita's purity. Nonetheless, the people did not trust her, therefore I sent her away, although I knew her to be sinless. I beg her forgiveness.'

Sita advanced into the middle of the assembly. In full view of all, with her eyes cast downwards, she made a vow.

'If I have always been faithful to Rama, in mind, word and deed, may Mother Earth embrace me. If I know only Rama as my worshipful lord, let her take me now.'

At that moment the Earth goddess rose from the earth on a beautiful throne. She took Sita in her arms and sat her on the throne, then withdrew with her into the earth. Petals fell from the sky and cries of adoration echoed from the gods.

Rama sank back in tears. He raged at the earth to return Sita, threatening to break down her mountains and over flood her surface. It was necessary for Brahma to appear before Rama and pacify him by reminding him that, as Vishnu, he would be reunited with Sita in heaven.

Rama mastered his grief. He returned to ruling his 4 kingdom and caring for his people. In time, he installed his sons and his brother's sons as rulers. Eleven thousand years passed by.

One day a strange figure appeared at his door. It was Death personified, sent with a message from Brahma. The message said, 'You are the eternal Vishnu who sleeps on the causal ocean. In ancient times I, the creator, was born from you. In order to kill Ravana, you entered the world of humans and fixed your stay for eleven thousand years. That time is now complete. Please return to protect the gods.'

Rama set off for the banks of the Sarayu river, taking with him his brothers and all who were devoted to him. Ayodhya was without a living soul. Only Hanuman, Vibhisana and Jambavan remained on earth. Entering the waters of the Sarayu with his devoted followers, Rama left this world and returned to his eternal realm, where his devotees eternally serve the Lord of their hearts, forever reunited with his beloved Sita.

Writer Name: Ranchor Prime

This thanka represents the refuge tree of the Ge-lug-pa school, representing the paths of Buddhism. and its propagation in Tibet. The central figure is Buddha Sakyamuni in blumisparsamudra and around him in all directions are grouped the Bodhisattvas, saints, propagators and protective deities of the Mahayana Buddhism. Buddha with an image of Adi Buddha Vajradhara in yab-yum at heart is flanked by Bodhisattva Maitreya and Manjusri on either side. On top of the thanka, in the middle, is portrayed the figure of Vajradhara and his Sakti in yab-yum, mahasiddhas, Bodhisattva Manjusri, Atisa, Tsong-kha-pa and the lineage of the Ge-lug-pa school. To the right and left of Buddha are grouped the Indian and Tibetan saints of the Vajrayana Buddhism.

This thanka represents the refuge tree of the Ge-lug-pa school, representing the paths of Buddhism. and its propagation in Tibet. The central figure is Buddha Sakyamuni in blumisparsamudra and around him in all directions are grouped the Bodhisattvas, saints, propagators and protective deities of the Mahayana Buddhism. Buddha with an image of Adi Buddha Vajradhara in yab-yum at heart is flanked by Bodhisattva Maitreya and Manjusri on either side. On top of the thanka, in the middle, is portrayed the figure of Vajradhara and his Sakti in yab-yum, mahasiddhas, Bodhisattva Manjusri, Atisa, Tsong-kha-pa and the lineage of the Ge-lug-pa school. To the right and left of Buddha are grouped the Indian and Tibetan saints of the Vajrayana Buddhism.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)