Unlike the widely scattered courts of Rajasthan, the numerous minor Rajput kingdoms of the Himalayan foothills were clustered in an area only three hundred miles long by a hundred wide. Although they shared a similar cultural background to the southern Rajputcourts, they were effectively separated from them by the broad expanse of the Punjab plains, and they were also less affected by Mughal incursions. This comparative isolation, together with the closer communications between the Hill courts, contributed to the development of some of the most expressive styles of Indian painting, characterised in their earlier phases by a controlled vehemence of colour and line, and later by a mellifluous idiom that combined Mughal technique with Rajput devotional and romantic sensibility.

The origins of the first classic style of Pahari (Hill) painting, associated with the court of Basohli, are still not understood, though it may have had antecedents in the widespread pre-Mughal style as well as in local Hill idioms. An early illustration to the Rasamanjari, a poetical text classifying lovers and their behaviour, reveals a fully formed and highly charged style, with a taut line and vibrant palette. The interpretation of literary conceits is as direct as in Rajasthani manuscripts.

![The month of Aghan, from a Barahmasa series of the twelve months The month of Aghan, from a Barahmasa series of the twelve months]() A lady who has been secretly unfaithful explains to her confidante that the love-marks on her breast were in fact scratches caused by the household cat as it chased a rat during the night. The cat and the rat appear on the pavilion roofer here is nothing here of the hybrid weakness sometimes found in Rajasthani work affected by Popular Mughal fluence. So confident was the Pahari artists' vision that Mugha portraiture could be reinterpreted with equal intensity. The Mankot raja with a rosary, huqqa and sword is not a psychological study of an individual but a celebration of the proud Rajput type silhouetted against a hot yellow background, orange bolster and white floorsprcad. Painting at the court of Kulu had a particular wildness and zest, Kuutala raga, from an extended ragamala series of the Pahari type, is depicted as a prince feeding pigeons; Akbar himself had been fond of the sport of pigeon-flying, which was known as ishq-bazi or love-play'.

A lady who has been secretly unfaithful explains to her confidante that the love-marks on her breast were in fact scratches caused by the household cat as it chased a rat during the night. The cat and the rat appear on the pavilion roofer here is nothing here of the hybrid weakness sometimes found in Rajasthani work affected by Popular Mughal fluence. So confident was the Pahari artists' vision that Mugha portraiture could be reinterpreted with equal intensity. The Mankot raja with a rosary, huqqa and sword is not a psychological study of an individual but a celebration of the proud Rajput type silhouetted against a hot yellow background, orange bolster and white floorsprcad. Painting at the court of Kulu had a particular wildness and zest, Kuutala raga, from an extended ragamala series of the Pahari type, is depicted as a prince feeding pigeons; Akbar himself had been fond of the sport of pigeon-flying, which was known as ishq-bazi or love-play'.

A lady who has been secretly unfaithful explains to her confidante that the love-marks on her breast were in fact scratches caused by the household cat as it chased a rat during the night. The cat and the rat appear on the pavilion roofer here is nothing here of the hybrid weakness sometimes found in Rajasthani work affected by Popular Mughal fluence. So confident was the Pahari artists' vision that Mugha portraiture could be reinterpreted with equal intensity. The Mankot raja with a rosary, huqqa and sword is not a psychological study of an individual but a celebration of the proud Rajput type silhouetted against a hot yellow background, orange bolster and white floorsprcad. Painting at the court of Kulu had a particular wildness and zest, Kuutala raga, from an extended ragamala series of the Pahari type, is depicted as a prince feeding pigeons; Akbar himself had been fond of the sport of pigeon-flying, which was known as ishq-bazi or love-play'.

A lady who has been secretly unfaithful explains to her confidante that the love-marks on her breast were in fact scratches caused by the household cat as it chased a rat during the night. The cat and the rat appear on the pavilion roofer here is nothing here of the hybrid weakness sometimes found in Rajasthani work affected by Popular Mughal fluence. So confident was the Pahari artists' vision that Mugha portraiture could be reinterpreted with equal intensity. The Mankot raja with a rosary, huqqa and sword is not a psychological study of an individual but a celebration of the proud Rajput type silhouetted against a hot yellow background, orange bolster and white floorsprcad. Painting at the court of Kulu had a particular wildness and zest, Kuutala raga, from an extended ragamala series of the Pahari type, is depicted as a prince feeding pigeons; Akbar himself had been fond of the sport of pigeon-flying, which was known as ishq-bazi or love-play'. Although there is some evidence of strongly Mughal-influenced work in the Hills in the late 17th century, comparable to that of the Bikaner school, this was exceptional during the first phase of Pahari painting. But in the second quarter of the 18th century a fundamental change of direction took place. Artists trained in the Mughal style began to arrive in increasing numbers, particularly after the sack of Delhi in 1739. From being the vehicle of a jaded sensuality, their technique became revitalised in lyrical depictions of Hindu poetical and devotional subjects, in a development paralleled in Rajasthan by the less subtle Kishangarh style.

Members of the family of the artist Pandit Seu, who were based at Guler but travelled widely among the Hill courts, were influential in shaping and disseminating the new style. One of Seu's sons was the great portrait artist Nainsukh, who had probably received some Mughal training. He enjoyed an unusually intimate and understanding relationship with his patronkthe minor prince Balwant Singh, whom he portrayed carrying out all the daily activities of a nobleman: hunting, listening to music, inspecting a horse, or simply writing a letter or preparing to go to bed. Compared with the stark Mankot picture, Nainsukh's portraiture and spatial setting are far more naturalistic. Nevertheless the bold, geometrical arrangement of the architecture and back-ground areas remains typically Rajput.

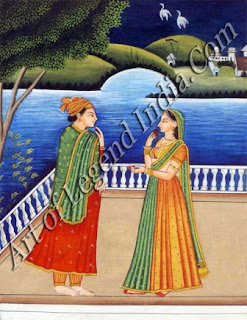

A religious subject in the early Guler style combines the new technical refinement with a devotional feeling taking the form of tender domestic observation Shiva is shown sewing a garment, while Parvati strings human heads for his necklace. Their sons, the many-headed Karttikcya and the elephant-headed Ganesha, who plays with Shiva's cobra, sit beside them, and their respective vehicles, the bull, lion, peacock and rat, wait in attendance Wersions of the graceful Guler idiom were developed at several courts, such as Garhwal to the south-east, where a Barahmasa illustration of the winter month of Aghan was painted a pair of lovers, idealised as Radha and Krishna, gaze at one another on a terrace while two cranes fly skywards.

The last great Pahari patron was Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra (1775-1823), whose long reign saw both the final maturity of Hill painting and the beginning of its decline. Early in his reign several masterly series of the classic texts celebrating the life of Krishna were illustrated for him. The love of Radha and Krishna was depicted with tender directness in idyllic landscape setting. As in earlier periods of Indian painting, the luxuriant burgeoning of nature serves to enhance and express the emotions of the human figures. (Krishna is as usual shown as an elegant, princely figure; perhaps akin to the young Sansar Chand. As at Guler, scenes of zenana life were also charmingly rendered, with increasingly curvilinear rhythms, as in a scene of ladies throwing powder and squirting water at the spring festival of Holi. But, as at Kishangarh, such a sweetly refined style could only remain fresh for a short time.

The last great Pahari patron was Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra (1775-1823), whose long reign saw both the final maturity of Hill painting and the beginning of its decline. Early in his reign several masterly series of the classic texts celebrating the life of Krishna were illustrated for him. The love of Radha and Krishna was depicted with tender directness in idyllic landscape setting. As in earlier periods of Indian painting, the luxuriant burgeoning of nature serves to enhance and express the emotions of the human figures. (Krishna is as usual shown as an elegant, princely figure; perhaps akin to the young Sansar Chand. As at Guler, scenes of zenana life were also charmingly rendered, with increasingly curvilinear rhythms, as in a scene of ladies throwing powder and squirting water at the spring festival of Holi. But, as at Kishangarh, such a sweetly refined style could only remain fresh for a short time.  From the beginning of the 19thcentury it became facile and sentimental. At the same time, Sansar Chand's power was lost first to Gurkha invaders and then to the Sikhs, who had won control of the Punjab plains and now began to annexe the Hill kingdoms. However, the British traveller William Moorcroft, who visited Sansar Chand in 1820, reports that, though living in reduced circumstances, he was still 'fond of drawing' and continued to support several artists as well as a zenana of three hundred ladies. His daily life was still passed in an orderly round of prayer, conversation, chess, viewing pictures and performances of music and dance.

From the beginning of the 19thcentury it became facile and sentimental. At the same time, Sansar Chand's power was lost first to Gurkha invaders and then to the Sikhs, who had won control of the Punjab plains and now began to annexe the Hill kingdoms. However, the British traveller William Moorcroft, who visited Sansar Chand in 1820, reports that, though living in reduced circumstances, he was still 'fond of drawing' and continued to support several artists as well as a zenana of three hundred ladies. His daily life was still passed in an orderly round of prayer, conversation, chess, viewing pictures and performances of music and dance. The Sikhs continued to hold the Punjab until their displacement by the British in 1849. They commissioned portraits of their Gurus and themselves in a weakened Pahari manner, to which they brought little inspiration as patrons. However one of the most imposing of all Indian portraits is that of Maharaja Gulab Singh. His large figure which fills the picture area is shown seated holding the familiar props of a sprig of flowers and a sword. He wears a dextrously composed turban and coat with sharply ruffled hem, and his face, no longer in profile, stares obliquely away from the viewer in baleful self-possession.

Writer – Andrew T0psfield