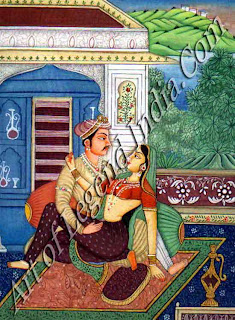

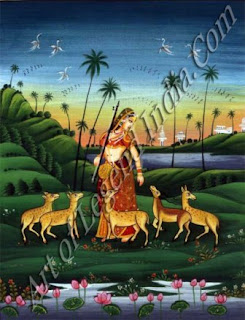

Beside Pampa Lake the season of spring had carpeted the soft turf with 'blue and yellow flowers, covered the trees and creepers in blossom, and wafted black honeybees among the perfumed blooms. Creepers embraced the trees like amorous young women with their lovers cuckoos sang love-songs and peacocks danced.

Rama could think only of Sita. The lotus flowers on the lake reminded him of her; he heard her calling him to see the beauty of the waterfalls and smelled her in the scented flowers. Without her, he could not live.

Perhaps she will give up her life when she sees spring without me,' he spoke aloud. 'If she would come to me now, I would be satisfied here forever, and would never wish again for Ayodhya or even the pleasures of paradise.

Be patient,' said Lakshmana. 'Now is the time for heroism and determination, not grief and despondency. We must find her wherever Ravana has hidden her.

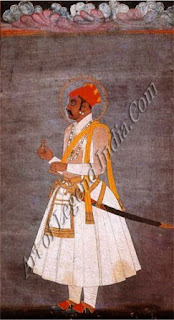

One day Sugriva, lord of the monkey tribes called the Vanaras, came near the lake to gather fruits and spied them. When he saw those two mighty princes he froze in fear, thinking them allies of his enemy Vali. He hurried back to his lair and called together his counsellors.

Vali has sent two powerful warriors, disguised as hermits. How shall we protect ourselves? Among his followers was Hanuman, son of the Wind god, who was wise and fearless. He counselled Sugriva.

These are no ordinary men,' replied Sugriva. 'They look more like gods, and they may be with Vali. Go and observe them closely and find out their business.

Hanuman disguised himself as a forest hermit and approached the two brothers. Bowing before them, he spoke with gentle words.

I salute you. With eyes like lotuses and weapons of gold you look like the Moon god and Sun god. I am Hanuman, son of the Wind god, minister of the monkey-lord Sugriva. Pray tell me who you are and what brings you here.

Hanuman's words showed him to be learned and gentle, and Rama answered him with respect. 'I am Rama, son of Dasaratha, and this is my brother Lakshmana.' He went on to say how they came to be in the forest, and how Sita had been kidnapped. 'We know of Sugriva and we seek his friendship and help,' said Lakshmana.

Hanuman thought these two men would be valuable allies for Sugriva. He in turn told them how Sugriva had been exiled and how he had lost his wife at the hands of his cruel brother Vali. 'Come, I will take you to Sugriva,' he concluded. Revealing his true monkey form, he lifted the brothers onto his shoulders and carried them through the forest to Sugriva's camp on Rishyamukha Hill. Arriving among Sugriva's assembly, Hanuman introduced Rama and explained that he needed help.

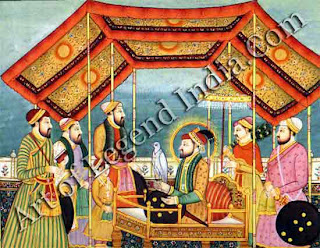

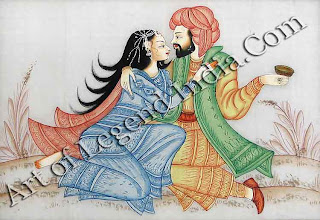

I am indeed fortunate,' said Sugriva, rising to greet Rama. 'Here is my hand in token of my friendship, if you will accept it.' Rama gladly clasped Sugriva's hand and warmly embraced him. Then Hanuman lit a fire between the two and together they walked around it to seal their alliance.

We are now united as friends, and our joys and sorrows are one,' declared Sugriva, hugely satisfied. Breaking off a large leafy branch from a nearby tree he offered it to Rama as a seat and sat beside him, while Hanuman did the same, breaking another branch and sharing it with Lakshmana. Sugriva then confided in Rama.

Don't worry,' reassured Rama. 'You have my word that I shall hill this Vali and help you recover your wife.

I have some news for you about Sita,' spoke Sugriva. 'I was sitting with four friends on top of the hill some days ago when we saw a strange sight. Passing over us in the air was a princess struggling in the arms of Ravana. As they flew above us she threw down a wrapper containing shining jewels.' He showed Rama the jewels. Instantly recognizing them, Rama could not hold back his tears, and cried, 'My darling!' holding them to his heart.

Tell me where Ravana has taken her and I will send him to his death this very day, he swore.

I do not know where Ravana lives or where he has taken Sita,' confessed Sugriva, but I give you my word that I and my monkeys will find her. Do not give way to this overwhelming grief. As your friend I beg you to be manful and restrain your tears.'

I am thankful for your words of advice,' said Rama. 'You are a true friend in time of need. But tell me, how can I help you?

Sugriva told Rama his story. Vail, his elder brother, son of Indra the Rain god, was ruler of the Vanara kingdom of Kiskindha. One day the demon Mayavi challenged Vali to a duel. Taking Sugriva with him, Vali went to face him, but the demon fled. They gave chase, and Mayavi hid in a deep cave. Ordering his brother to stand guard outside the cave, Vali went in after him. A year passed and still he had not returned, so Sugriva, thinking his brother dead, sealed the mouth of the cave with a large stone and returned to Kiskindha, where he was crowned king in Vali's place. Meanwhile, Vali killed Mayavi and escaped from the cave, arriving back in his kingdom to find Sugriva on the throne. In fury he denounced him, seized his wife and banished him.

Since then I have lived in fear, wandering the forests and hills until I found shelter here in Rishyamukha, the only place where Vali cannot harm me. lie can throw mountain peaks in the air and catch them and tear up large trees at will. But once he fought the demon Dundubhi, killing him by throwing him a distance of four miles. The demon's body landed near this place and splashed blood on the sage Matanga. He was so disturbed by this intrusion that he cursed Vali that if he or any of his monkeys ever set foot here they would be turned to stone. That is why we live here, because it is the only place where we are safe from him.

Now that you know the strength of Vali, you will surely understand if I doubt whether you are strong enough to oppose him. No one has ever defeated him in combat, so how do I know you can do it? The skeleton of the demon Dundubhi lies nearby. If you can throw it with your foot a distance of one thousand yards, then you may be strong enough.

Rama took up this challenge and, lifting the carcass with his toe, tossed it a hundred miles. But Sugriva was not satisfied.

The carcass is dried up and lighter than when Vali threw it. I have another test for you. Sometimes Vali used to pierce these sal trees to practice his archery, splitting the trunk of a tree in two. If you can do that you are strong enough to defeat him.

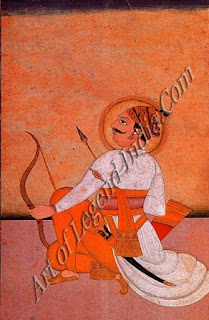

Close by were seven sal trees in a row. Rama took an arrow from his quiver and shot it from his bow. It passed through each of the trees in turn, then penetrated the earth as Far as the underworld before bursting out again minutes later and re-entering his quiver. After seeing this feat, Sugriva bowed low in astonishment and was fully convinced of Rama's power to defeat Vali.

Come then,' said Rama. 'Let us go to Kiskindha where you can challenge your brother to a duel.

Kiskindha, the capital of the Vanara kingdom, was built around a series of under-ground caves, with carved pillars and cascades of water. Here Vali lived in comfort with his wives. His peace was disturbed by the roaring of Sugriva, who stood outside challenging him to duel, with Rama concealed in the forest nearby.

The two brothers met with a thunderous clash, like Mercury crashing into Mars. Rama, concealed behind a tree, watched closely, his bow at the ready, waiting for an opportunity to strike Vali. But he was baffled. The brothers appeared identical and it was impossible for him to be sure which one was Vali.

Eventually Vali got the upper hand and Sugriva, battered and bleeding, was forced to retreat, running for his life to the safety of Rishyamukha. When Rama returned Sugriva was dismayed.

You encouraged me to fight with Vali,' said Sugriva, 'saying you would kill him. But now I see it is as I feared: you don't have the strength to do it.'

Let me explain,' replied Rama. 'I was unable to tell you and Vali apart and did not dare fire my arrow in case I killed you by accident. Next time you must wear some distinguishing mark.' So Lakshmana made a garland of' flowering creepers and put it around Sugriva's neck, and they went back a second time.

At the entrance to kiskindha, Sugriva let out a roar which split the air, frightening away all the forest animals. In response, Vali shook with rage and prepared to meet him. But his wife, Tara, was anxious.

Quell your anger and don't let yourself be provoked. I feel uneasy about Sugriva coming a second time. I have heard that he has made friendship with Rama, son of the emperor of Ayodhya, who is invincible in battle. My advice is that you abandon this quarrel with your brother. Make him prince regent and give him gifts, and befriend Rama as well.' But Vali, in the grip of fate, did not heed Tara's advice.

Why should I put up with his arrogance?' said Vali. 'And besides, Rama would never harm an innocent person such as me. I will fight again with Sugriva, so long as he stands up to me. He will soon run away again when he feels the blows of' my fists.

Why should I put up with his arrogance?' said Vali. 'And besides, Rama would never harm an innocent person such as me. I will fight again with Sugriva, so long as he stands up to me. He will soon run away again when he feels the blows of' my fists. So Vali sallied forth, hissing like a snake. His brother Sugriva, shining golden-brown, tightened his cloth and waited for him. The two met once more, colliding like two bulls. Vali smashed Sugriva with his fist, making him vomit blood. Then Sugriva tore up a tree and struck Vali to the ground, making him shake. They locked in combat, each effulgent like the moon and sun in the sky. They fought with tree trunks, boulders, fists, feet, arms and legs, roaming about the forest smeared in blood like two storm clouds.

Vali started to get the upper hand and Sugriva desperately looked around for Rama. Seeing his chance, Rama let loose an arrow tipped with gold and silver. With a thunderous flash it tore into Vali's breast and knocked him to the ground. Uttering a cry of pain, he lay motionless. He was mortally wounded but he still had the strength to speak. He saw Rama with his bow and accused him.

This is a cruel and dishonorable act, to kill someone who was not fighting against you. I never thought you would stoop to attack me in such a way. I did nothing against you. I am an innocent monkey who lived in the forest eating only fruits and roots. Though you are born to be a king, you have no rights over me. You are a ruler of men, whereas I am a beast of the jungle who has done you no harm. What do you have to say in defense of your brutal behavior?' Vali lapsed into silence, his mouth parched and his body racked with pain. Rama answered Vali with respect.

This is a cruel and dishonorable act, to kill someone who was not fighting against you. I never thought you would stoop to attack me in such a way. I did nothing against you. I am an innocent monkey who lived in the forest eating only fruits and roots. Though you are born to be a king, you have no rights over me. You are a ruler of men, whereas I am a beast of the jungle who has done you no harm. What do you have to say in defense of your brutal behavior?' Vali lapsed into silence, his mouth parched and his body racked with pain. Rama answered Vali with respect. Why do you reproach me? Listen to the reasons for my action. My brother Bharata is emperor of these lands and it is my duty, under his command, to uphold justice throughout his kingdom.

You failed to give due protection to your younger brother, who you should treat as your own son, and moreover, you took his wife, Rama. The punishment for one who has union with his brother's wife while his brother is alive is death.'

These are my reasons for slaying you, as well as to fulfill my word to your brother that I would help him recover his wife and his kingdom. I have acted as law-keeper for your own good, because the religious laws state that a criminal justly punished is absolved of sin and ascends to heaven just as the pious do. Thus I have released you from your sin and I have no regrets over what I have done.

Vail sighed. 'What you have done is correct. I see that you are indeed devoted to the good of all people with a clear and unruffled mind. I beg you to fulfill my last request. Please see that my son Angada, who is still a boy, is reconciled with Sugriva and cared For by him, and see that Sugriva treats my widow, Tara, with kindness.

Vail sighed. 'What you have done is correct. I see that you are indeed devoted to the good of all people with a clear and unruffled mind. I beg you to fulfill my last request. Please see that my son Angada, who is still a boy, is reconciled with Sugriva and cared For by him, and see that Sugriva treats my widow, Tara, with kindness. Do not worry on this score,' Rama reassured him.

Forgive me,' whispered Vali.

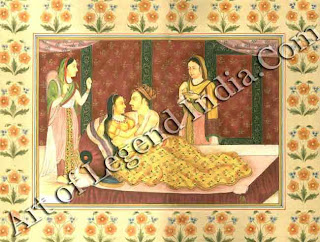

Hearing news of' her husband's condition, Tara hurried to him, crying and beating her head in agony. She came upon him lying on the ground like a spent cloud and clasped him to her bosom.

Why don't you speak to me, my great hero? Why does my heart not break into a thousand pieces to see you in this state? You have got your reward for banishing your brother and stealing his wife. If only you had heeded my advice. Here is your son. Come darling Angada, see your father for the last time.

Vali glimpsed his brother Sugriva standing before him.

Forgive me, brother,' he murmured, 'I was carried away by forces out of my control. I am about to leave for the abode of death, and I want you to take the throne and rule over Kiskindha. Please look after my son Angada as if he were your own, and be considerate to Tara and always listen to her advice, for she speaks the truth.' Finally he spoke to his son. 'Accept Sugriva as your protector and serve him with devotion. Do not be over-fond of others nor without affection, but always seek the balance.' With these words Vali breathed his last.

Sugriva was overcome with remorse after hearing his brother's dying words and thought of' ending his own life. in recompense. Tara also wanted to die.

You are wise and patient, she prayed to Rama. 'Please kill me with the same arrow that killed my husband, then I can be reunited with him.

Do not despair,' Rama comforted them, 'for this world is made up of happiness and sorrow in equal measure. Tara, you will yet And happiness under the protection of Sugriva, and your son will be prince regent, therefore do not lament.

Do not despair,' Rama comforted them, 'for this world is made up of happiness and sorrow in equal measure. Tara, you will yet And happiness under the protection of Sugriva, and your son will be prince regent, therefore do not lament. Rama then helped them with Vali's funeral. They carried his body in procession to a lonely spot by the river, where a funeral pyre was built and sacred hymns were chanted. As the hills echoed to the crying of his wives and the Vanara women, his body was enveloped in flames and he departed on his long journey to the next world. Rama patiently watched as Sugriva and his companions bathed in the river to purify themselves then came towards him. Hanuman spoke up.

We will now take Sugriva to Kiskindha and crown him. After he has been ceremonially anointed and bathed according to our customs, please come and feast with us in our capital.'

Thank you, Hanuman,' replied Rama, 'but I cannot indulge in the comforts of Kiskindha. I must keep my vow to my father and stay in the forest until my fourteen years are up.

Thus Sugriva, with the help of Rama, got back his wife Rama and his kingdom and lived happily. Meanwhile, the monsoon season began and the rains made it impossible for Rama and his new allies to track down Ravana.

You all enjoy yourselves,' said Rama. 'I will live with Lakshmana in this cave which is dry and airy with a nearby waterfall. In four months, when the rains are over, our search for Sita will begin.

Gathering the Tribes

The rains intensified and Sugriva and Rama retired to their caves: Sugriva to the comfort of the cave-city of Kiskindha, and Rama to his hermit's cave in the forest.

The rains intensified and Sugriva and Rama retired to their caves: Sugriva to the comfort of the cave-city of Kiskindha, and Rama to his hermit's cave in the forest. The cave chosen by Rama and Lakshmana was ideal for their needs. It was near the wooded summit of Prasravana Hill, deep and dry and well sheltered from the rain-laden easterly winds. Close by was a rocky pool of lotus flowers and not far away a broad river with sandy banks.

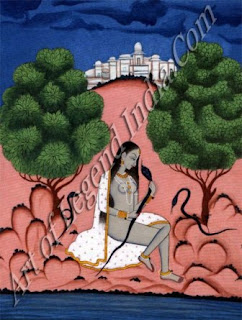

Sitting at the entrance of the cave, Rama looked out through the rain. The earth steamed and dark clouds lashed the mountain sides. The flashes of' lightning inside the dark clouds seemed to him like Sita struggling in the arms of Ravana, and the rain seemed like her tears.

The heat and dust of summer subsided and tracks became muddy and impassable. Mountain streams rushed to the sea, strewn with flowers and reddened by the earth, flocks of swans migrated to their northern homes and flights of' herons flew beneath the clouds pealing with thunder.

Rama lay awake in the moonlit nights thinking of Sita. In the distance he could hear the beating drums and festive singing of the monkeys celebrating Sugriva's victory.

Sugriva is enjoying his change of fortune,' he thought, 'while I have lost everything. But it is not yet time to act. We must wait for the rains to end, when Sugriva will remember his obligation to me.'

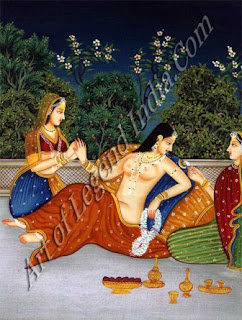

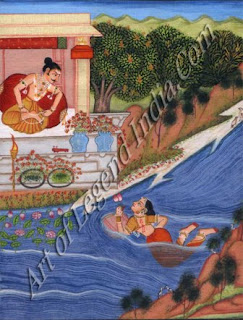

After four months Hanuman looked out and saw the sky clear and bright. The rains were over and the time had come to repay the debt to Rama. He went to Sugriva and found him intoxicated in the embrace of his wife Rama.

Do not forget your friend Rama who has done you good service by killing Vali,' reproved Hanuman. 'He is waiting to hear what you are doing to help him find Sita.' Sugriva was stirred into action.

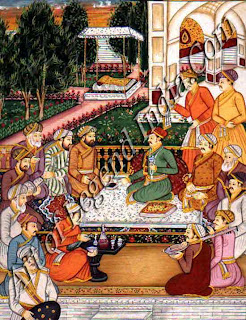

Call for Nila,' he commanded. 'Tell him to muster monkey troops from near and far. All monkey-warriors must be here within fifteen days under pain of' death.' Sugriva then returned to the arms of his mistresses.

But Rama heard nothing. He felt the change of season as the warm autumn nights drew in under a clear sky. He called Lakshmana.

But Rama heard nothing. He felt the change of season as the warm autumn nights drew in under a clear sky. He called Lakshmana. Go and speak with Sugriva. Tell him not to forget that it was I who killed Vali, and warn him that jibe does not help me I am quite capable of killing him too!

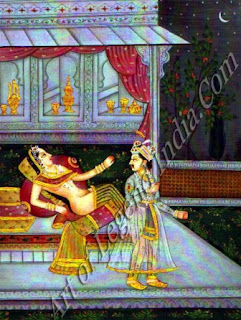

Lakshmana set off in earnest to confront Sugriva. As he angrily entered the caves of Kiskindha the guards fled to inform Sugriva of his arrival. Sugriva, however, was in a drunken stupor in the midst of his lovers. Hanuman impressed upon him the seriousness of' the situation.

You have lost track of time. Now go quickly and appease Lakshmana,' he urged.. 'Bow low before him and offer to do whatever Rama pleases.

Lakshmana was ushered into Sugriva's private apartments. He saw beautiful girls decorated with tinkling ornaments. The lovely Tara, now Sugriva's wife, emerged in a languid state, slightly intoxicated with her girdle loosened.

What displeases you, Prince Lakshmana?' she enquired softly.

Your husband appears to have forgotten his duty,' replied Lakshmana. 'For the last four months he has indulged in wine and love-making and seems unaware that it is now time to fulfill his duty to Rama. I have come to remind him.

Please forgive my husband, who forgets the passing of time when under the sway of passion. However, he has already sent for thousands and millions of monkeys, and has quite shaken off his sensuous mood.' Tara beckoned him into Sugriva's presence, where he beheld Sugriva lying like a god on a soft couch embracing Rama and served by young women, his eyes rolling with intoxication. Lakshmana angrily rebuked him. 'You are decadent and ungrateful.

You have accepted Rama's services but have not returned them. Rama wishes me to warn you that if you do not honour your agreement with him you will go the way Vali went.' Sugriva got up quickly, scattering his women like the moon carrying stars in its wake.

You have accepted Rama's services but have not returned them. Rama wishes me to warn you that if you do not honour your agreement with him you will go the way Vali went.' Sugriva got up quickly, scattering his women like the moon carrying stars in its wake. Do not speak harshly to my husband,' pleaded Tara, he meant no harm. To please

Rama he would give up his throne and even Rama and myself. He is prepared to kill Ravana, but we must first defeat Ravana's army, which is said to consist of a thousand billion rakshasas. Therefore we have sent for millions of monkeys, baboons and bears From the four quarters to assemble here. Today they are due to arrive.

After Lakshmana had been placated by Tara's words, Sugriva ventured to speak. 'I owe my good fortune to Rama and I will repay him. Ask him to forgive me.' 'Forgive my harsh words, spoken out of concern for Rama,' countered Lakshmana.

Now come with me to reassure him.' 'First I must organize the gathering of' my troops.' Sugriva called again for his commander Nila. 'Send out a second wave of messengers to hasten the mustering of forces from the far-flung mountain ranges of Himalaya, Mahendra, Vindhya, Kailash and Mandara. All must gather here within ten days. Especially attend to those who are sensuous and lazy. Tell them they must obey my royal command or suffer death. In a moment these messengers took to the air. Flying with the speed of mind along the migratory routes of the birds, they fanned out across the world to gather monkeys from seashores, mountains, forests and lakesides.

A vast horde of monkeys assembled black monkeys from Anjana mountain, golden monkeys from the forests of the sunset, monkeys like lions from Kailash mountain, red monkeys from the Vidhya heights, others from the Himalaya range and the shores of the Milk Ocean. When all was in hand Lakshmana took Sugriva before Rama, to whom he bowed low.

Now the time has come for our great adventure,' said Rama.

At this very moment,' announced Dugriva, 'the leaders of' monkeys, bears and baboons are on their way to join us from all over the world, followed by troops numbering thousands of' millions.'

At this very moment,' announced Dugriva, 'the leaders of' monkeys, bears and baboons are on their way to join us from all over the world, followed by troops numbering thousands of' millions.' Rama embraced him. As they spoke a dust-cloud rose from all sides veiling the sun The sky darkened and the earth vibrated with the rumble of millions of feet as innumerable monkeys poured into the valley from all sides, led by their illustrious chiefs, each with the power to light single-handedly with the gods. One by one the chiefs came forward to identify themselves to Sugriva and bow to Rama before being assigned a place for their troops.

Now what would you have us do, lord?' asked Sugriva.

First we must find out if Sita is still alive and where she is being held.' said Rama. 'Once we know that, we will decide upon our course of action.

Sugriva called the chiefs together and divided them into four parties, each of which was assigned a different direction: east, south, west and north. They were told to search all the lands as far as the great mountains encircling the earth, beyond which no human or monkey is allowed to pass, and to return within one month. Whoever found Sita was promised ample reward. Among these chiefs, Hanuman was sent south with Angada, son of Vali, Nila, son of the Fire god, and Jambavan, lord of the bears and son of Brahma. Sugriva spoke with Hanuman.

None is your equal, Hanuman. You have the speed and agility of your father, the Wind god. I am relying on you to find Sita.' Seeing Sugriva's confidence in Hanuman, Rama was convinced that he was the one who would find Sita, so he took him aside and spoke with him.

Take this ring inscribed with my name and give it to Sita, so that she will know you to be my servant. Your courage and determination guarantee your success. I am depending on you.

Hanuman took the ring, touched it to his head and then bowed at Lord Rama's feet. Shining like the moon in a clear sky; he set off with the sound of Rama's words ringing in his ears.

The Search for Sita

Once the teams of searchers had been dispatched, Sugriva returned to his life of leisure and Rama to waiting. A month passed and the searchers from the east, north and west returned empty-handed.

We have explored the mountains, forests, rivers and seas. We have ransacked caves and dense thickets, and we have encountered and killed large demons, suspecting them to be Ravana. But we have found no sign of Sitai our only hope now lies with Hanuman.'

Hanuman's party, however, was not to be seen. They had gone south, the direction in which it was known Sita had been carried, over the Vindhya mountains to the desert beyond, which was without water or food. With their strength and hope fading, they criss-crossed the region again and again, finding no trace of' Sita.

When their month was nearly up, exhausted from hunger and thirst, they came to the mouth of a deep cave on the southern tip of the Indian peninsula. From inside the cave came a flow of cool, moist air and around its mouth grew dense green foliage.

Herons and swans emerged from the cave, their plumes wet and stained with the red pollen of lotuses. They decided to venture inside the cave in search of water.

Holding hands, they penetrated the darkness. For a long time all was dark as they journeyed ever deeper. Then they saw light ahead and heard the tinkling of running water. They emerged into a cavern illuminated by a clear, soft light where they found trees of gold, mansions of silver and gold, luscious fruits and heaps of gems. Gratefully they satisfied their hunger and thirst and restored their strength and spirits. Then they looked about them and saw the figure of a woman dressed in deer skin and bark, shining with an aura of' saintliness. Hanuman asked her who she was and to whom the cave belonged.

Holding hands, they penetrated the darkness. For a long time all was dark as they journeyed ever deeper. Then they saw light ahead and heard the tinkling of running water. They emerged into a cavern illuminated by a clear, soft light where they found trees of gold, mansions of silver and gold, luscious fruits and heaps of gems. Gratefully they satisfied their hunger and thirst and restored their strength and spirits. Then they looked about them and saw the figure of a woman dressed in deer skin and bark, shining with an aura of' saintliness. Hanuman asked her who she was and to whom the cave belonged. This cave was the home of the demon Maya, who embellished it by his mystic art, but was slain by Indra. I am Svayamprabha, sent here to be its guardian.' Hanuman told her of their search for Sita.

Goddess, our strength is now restored by your generosity. How can we repay you?' 'I want nothing from you, but tell me how I can help you,' she replied.

Show us out of this place. We must return to our king, Sugriva, by the appointed time.' She instructed them to close their eyes and in an instant they were once more in the bright sunlight outside the cave.

As their eyes grew accustomed to the daylight they saw that the season of spring was already far advanced, the trees being heavy with blossom. Fear gripped them as they realized that their allotted month was past. If they returned now, without any news of Sita, Sugriva would kill them.

In despair they decided to fast to death. Weeping, they sat down and prepared to die. However, a more immediate danger faced the monkeys. From far above unseen eyes saw them as a tasty meal sent by providence. Sampati, king of the vultures and older brother of Jatayu, was perched on the mountainside above the monkeys. He had not eaten for a long time, because he was crippled by the loss of his wings.

I shall eat each of these monkeys one by one as they die of starvation,' he said. The monkeys heard this and looked up to see the huge vulture.

Jatayu, lord of vultures, gave his life for Rama,' protested Angada. 'Must we, who have sacrificed so much in the service of Rama, be eaten by this vulture?' Sampati was bewildered to hear mention of his brother Jatayu, and the name of Rama, who he knew to be the glorious son of Emperor Dasaratha.

Jatayu, lord of vultures, gave his life for Rama,' protested Angada. 'Must we, who have sacrificed so much in the service of Rama, be eaten by this vulture?' Sampati was bewildered to hear mention of his brother Jatayu, and the name of Rama, who he knew to be the glorious son of Emperor Dasaratha. Who is it that speaks of Jatayu, my brother, and of Rama, son of Dasaratha? Help me down from my perch so that I may speak with you.

The monkeys, who were past caring, thought they may as well die as food for this venerable vulture as by starvation, so they helped him down. They told Sampati the full story of Sita's abduction, Jatayu's death and the monkey's failure to find Sita and their consequent state of despair. Sampati was distressed to hear of the death of his younger brother Jatayu, and eager to help in the search for Sita.

I will not eat you,' he said. `Instead I can help you find Sita. I once saw from this mountain a beautiful young woman carried through the air by Ravana, calling the names "Rama! Lakshmana!"

This was surely Sita,' exclaimed Hanuman. 'Where did Ravana take her?' 'Ravana lives in the city of Lanka on an island a thousand miles out to sea. Sita is held captive there by Ravana.

On hearing Sampati's information the monkeys leapt to their feet, all thoughts of starvation banished from their minds. Excitedly they took leave of Sampati and made their way to the nearby shore of the Indian Ocean. Looking across the southern sea they saw only the vast expanse of water and their hearts began to sink. How could they cross such a great distance as a thousand miles? Each of them estimated his ability in leaping: some said they could leap one hundred miles, some two, some five hundred, but none felt confident enough to cross to Lanka and back. ‘Jambavan turned to Hanuman, who had kept silent.

You are son of the Wind god and are equal to him in your power to fly through the air. When you were a child you saw the sun rising through the trees and mistook it for a fruit. You leapt into the sky to catch it, rising to a height of twenty thousand miles. In anger at your audacity, Indra hurled his thunderbolt at you and dashed you to the ground, breaking your jaw. Therefore you are called Hanuman, meaning 'one with a broken jaw'. To make up for this Indra blessed you to meet death only when you choose to die, and Brahma made you invulnerable in combat. Now show us your prowess by leaping across the vast ocean to Lanka.

While Jambavan spoke Hanuman shook off his depression and grew to a colossal size. Whirling his tail in delight, he prepared to leap across the ocean.

I can overtake the sun on its journey from east to west, or jump to the very ends of the earth, scattering clouds and shaking mountains. Certainly I will jump to Lanka.

Looking for a secure foothold from which to leap, giant Hanuman climbed the nearby Mount Mahendra. As he trod on it the mountain trembled, releasing new springs and alarming deer and elephants, driving snakes from their holes. Concentrating his mind, Hanuman fixed his thoughts on Lanka and the divine Sita, and prepared to jump.

Writer – Ranchor Prime