In ancient times the regions in and around Jaipur were known as Dhundar. Most parts of Alwar, Jaipur, Shekhawati are still called Dhundar Pradesh. Some scholars are of the opinion that this province acquired the name because of a demon called Dhund. But other scholars hold the view that this province, with shifting sand dunes, was recognised as Dhundar Pradesh.' The Dhund river might also be considered the principal basis for its name.

Under the banner of the Dhundar school, we may study the Amber, Jaipur, Alwar and Shekhawati styles, and the Uniara substyle among others. Dhundar Pradesh has its own distinct features and geographical boundaries. In touch with the centre of gravity of the administration, Delhi, and with the centre of culture, Braj, the Dhundar style of painting had continued its pace of development through various new forms from time to time.

Amber Style

The Amber style is the rich heritage of the rajas of the Kacchava and Kush dynasties. In the 10th-11thcenturies they had a large kingdom around Gwalior. In 1071, Sod Deo along with his son Dullaha Rai came to Dhundar Pradesh and steadily expanded their kingdom. Their descendants made Amber their capital, and this city held this position for seven centuries.' Ancient specimens of the Amber style of painting are not available. Frescoes drawn around 1600-1614 upon cenotaphs in Amber are the oldest available pieces of this style.' Paintings in the cenotaph of Bhar Mal acquire great significance from the historical point of view. Inside the cenotaph a panel of these 40 paintings depicts the early history of the Amber style.

![One of the winters month One of the winters month]() These paintings were drawn straight upon the stone without having made them in the prevalent Jaipur Arais style. Each painting is based upon a definite principle. According to subject matter these paintings include scenes of hunting, incarnation, wrestling, yoga, Laila-Majnu, rag-ragini, elephant, camel and fighting among animals.

These paintings were drawn straight upon the stone without having made them in the prevalent Jaipur Arais style. Each painting is based upon a definite principle. According to subject matter these paintings include scenes of hunting, incarnation, wrestling, yoga, Laila-Majnu, rag-ragini, elephant, camel and fighting among animals.

Original colours like garun, safeda , kaluns were used in these paintings. Drawing had been made either in red or black and colour was applied on the figures. The strong influence of the paintings of the period in reigns of Akbar and Jehangir is clearly discernible in these paintings. Besides the impact of artistic folk art a circular jamma with four pointed edges and Jehangiri turban are some special characteristics of these paintings. Women in Rajasthani attire, including ghagra, odhni, blouse, adorned with Mughal style ornaments are frequently seen in such paintings.

Besides the cenotaphs of Amber, frescoes in the Amber style may be noticed in the so-called Mughal garden of Bairath, in which themes like rag-ragini, Krishna-Lila, nayika-bhed, Laila-Majnu, wrestlers, elephant riding, horse riding, camel riding were painted. To study the early stage of the Amber style, these paintings deserve careful scrutiny.'

Mojamabad, adjoining Jaipur, was also a centre of the early Amber style. A cenotaph of Mojamabad which possessed frescoes in this style is now in ruins. The Amber style has been much influenced by the Mughal style.

In the middle of the 16thcentury the rajas of Rajasthan began to bow to the mighty Mughal Empire. In 1562, Akbar signified his good relations with the kingdom of Amber by marrying the daughter of Raja Bhar Mal. In the reign of Raja Man Singh (1589-1610), the Kacchava dynasty of Amber maintained very close relations with the Mughals.

The cenotaphs of Amber, the gardens of Bairath and Mojamabad, the birthplace of Raja Man Singh, have frescoes which were greatly influenced by the Mughal style. The famous pictorial text Rajina-Namali (1584-1588) compiled at the court of Akbar and preserved in the city Palace Museum, Jaipur, provides very useful information about the initial growth of the Amber style and details regarding artistic exchanges.

The second stage of development of this style commenced in the reign of Mirza Raja Jai Singh (1625-1667). The renowned Ritikaleen poet Bihari was one of his courtiers. Bihari-Satsai deeply influenced many artists. Paintings belonging to this age are rarely available. They exhibit the salient features of folk art (Pl. 30) and the impact of the Mughal school.

Salient Features

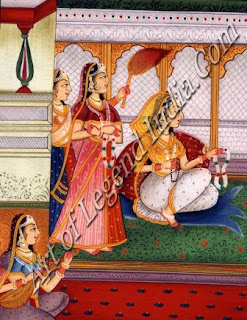

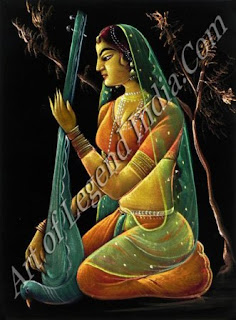

![A Rajput Princess Royally adorned A Rajput Princess Royally adorned]() The style possesses its own characteristics, in which the structure of bodies of both male and female has been much influenced by Rajasthani folk art. Because of their kinship with the Mughals mutual cultural exchange was natural. Hence the impact of ornamented dresses belonging to the periods of Akbar and Jehangir is discernible.

The style possesses its own characteristics, in which the structure of bodies of both male and female has been much influenced by Rajasthani folk art. Because of their kinship with the Mughals mutual cultural exchange was natural. Hence the impact of ornamented dresses belonging to the periods of Akbar and Jehangir is discernible.

Jamma with four pointed edges and later circular jamma and tight-fitting pyjama, Jehangiri turban style, dress like that worn by Chhagtai women, are quite visible in the Amber style. Black phulitline on hands hagra, odlmi are closely linked with Rajasthani style.

Poor quality of line is seen in the Apbhransh style, and so are natural colours like hirmich, kaluns, safeda, pewari, extensively used in the shape of animals, birds and trees as in folk art. In sum and substance, the Amber style has its own constitution quite visible in these frescoes and in some pictorial texts.

Jaipur Style

The Jaipur style has inherited the Amber style as a cultural legacy. Or it may be presumed that the Amber style itself grew in a new environment at the time of founding Jaipur city, and since then it has been called the Jaipur style. Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh laid the foundation of Jaipur in 1727 and constructed it as his new capital instead of Amber. He had the distinction of being a great astronomer, astrologer, mathematician and keen lover of art. Hence he had built many beautiful and majestic buildings like the observatory, Chandra Mahal, Jai Niwas Bagh, Talkatora, Sisodia Rani Palace and thus gave a new cultural direction to Jaipur.

Jaipur, because of is architectural charm, pleasant combination of colours and scientifically laid out plan, is known as the Pink City of India. Owing to its traditional miniatures, artistic cottage industries, existing festivals and colourful dress Jaipur has been a great cultural centre since its inception.

The newly laid out city attracted architects, artists and other learned personalities from every part of the country. The traditional Kacchava or Amber style preferred tender drawings. Because of the close ties with the Mughal court, the impact of the Mughal style became more pronounced in this period. Muhammad Shah was a court artist of great skill. Because of the powerful cultural impact of the Mughals some doubts about paintings of this period are often heard.

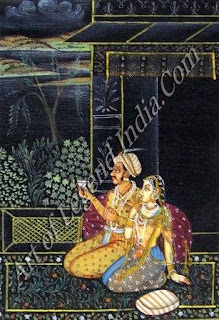

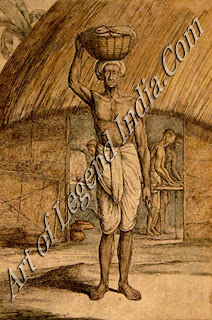

![Maiden Surprise at their bath Maiden Surprise at their bath]() Sawai Jai Singh's son Raja Ishwari Singh (1743-1750) was a great Tantric. In his reign he was engaged in a constant struggle with the Mahrattas and ended his life with a dose of poison. But in his short rule he constructed an iser latt to commemorate his victories over the Mahrattas.

Sawai Jai Singh's son Raja Ishwari Singh (1743-1750) was a great Tantric. In his reign he was engaged in a constant struggle with the Mahrattas and ended his life with a dose of poison. But in his short rule he constructed an iser latt to commemorate his victories over the Mahrattas.

In his time, Sahib Ram, a chittara, emerged as a talented artist. He painted a portrait of Raja Ishwari Singh with the help of Chandras which has been recognized as of high quality. Another famous artist of his period was Latt Chittara, who had painted many pictures depicting animals and birds in struggle. These pictures are very lively.

In the reign of Sawai Madho Singh I (1751-1767), consistent instability prevailed because of differences between Jats and Mahrattas, but still Sisodia Rani Palace and Chandra Palace were adorned with frescoes. The traditional frescoes of Jaipur had reached the portals of have! is. The havelis of Pundrik deserve special notice.

Sahib Ram earned the reputation of being a seasoned artist in this period. He painted large-sized portraits with Ramji Dass and Govindji, two more artists, while Lall Chittara continued to paint various royal sports. In paintings of this age the Mughal influence began to wane and a pure Rajput style showed signs of replacing it. In place of paintings the traditional ornamented Manikuttim style in which beads, red and wooden mannis, are pasted together, began to receive encouragement.

![After Bath After Bath]() The reign of Maharaja Prithvi Singh (1767-1779) was short. Artists patronised by the state continued to pursue their vocation. Court artists Hira Nand and Trilok earned great fame. In 1778 they drew a life-sized portrait of their maharaja.

The reign of Maharaja Prithvi Singh (1767-1779) was short. Artists patronised by the state continued to pursue their vocation. Court artists Hira Nand and Trilok earned great fame. In 1778 they drew a life-sized portrait of their maharaja.

With his sudden death his younger brother Sawai Pratap Singh (1779-i803) took charge of the administration. He was a keen lover of art and literature and he added new chapters to the development of artistic and literary activities in the state. He was drawn towards religion and poetry, and he composed poems under his pen name Braj Niddhi. He also dedicated himself to Pushti Marg, which had developed his devotion to the Krishna-Bhakti cult. Twenty-one texts he compiled are still available. The world famous Hawa Mahal was built in his regime. Pritam Niwas, adorned with traditionally artistic doors, Diwan-e-Aam, the upper floors of Chandra Mahal, were designed by him as well as built under his guidance.

As he was both poet and devotee many poets and artists congregated at his court. The seasoned artist Sahib Ram continued to practise his art there. Three pictures he painted have been hailed as unique specimens of his painting. Two are portraits of the maharaja and the third a dance pose of Radha-Krishna.

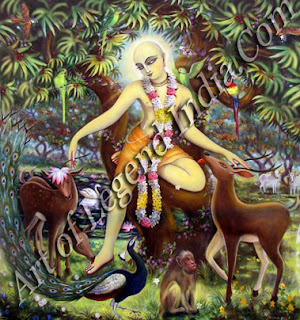

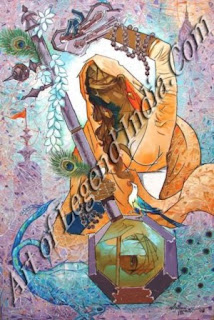

![Todi Ragini Todi Ragini]() In this period themes relating to this of Radha-Krishna, nayika-bheda, rag-ragini, ritu-varnan were extensively portrayed. Large-sized portraits of raja-rani, many paintings concerning Bhagwad-Puran, Durga-Saptshati, Krishna-Lila de-serve special mention here." Other artists besides Sahib Ram included Jeevan, Chassi, Salig Ram, Raghu Nath, Ram Sevak, Copal, Udai, Hukma, Chimna, Daya Ram, Raju, Niranjan who deserve special notice. They worked on both frescoes and miniatures in the Jaipur style.

In this period themes relating to this of Radha-Krishna, nayika-bheda, rag-ragini, ritu-varnan were extensively portrayed. Large-sized portraits of raja-rani, many paintings concerning Bhagwad-Puran, Durga-Saptshati, Krishna-Lila de-serve special mention here." Other artists besides Sahib Ram included Jeevan, Chassi, Salig Ram, Raghu Nath, Ram Sevak, Copal, Udai, Hukma, Chimna, Daya Ram, Raju, Niranjan who deserve special notice. They worked on both frescoes and miniatures in the Jaipur style.

This style of painting continued to flourish till the reign of Sawai Jagat Singh (1803-1818). The renowned traditional poet Padamakar lived in his court. He linked the Jaipur royal house with Bihari Satsai after having compiled. Jagad Vinod." Paintings titled Goverdhan Dharan and Ras-Mandal are exquisite examples of the art of that age.

After Sawai Jagat Singh the original form of the Jaipur style did not last long once the impact of British culture began to be felt. In the period of this maharaja, artists began to pursue painting in the representational style. Portraits were drawn like photographs.

After studying this new trend the maharaja set up the Maharaja's School of Arts and Crafts and thus gave a new direction to the local style of painting. According to his directive, the whole city was painted pink. The traditional beauty of Jaipur thus vanished into oblivion. The Jaipur style was not confined to the royal court but flourished and developed at adjoining centres belonging to feudal lords related to the Jaipur family. From time to time pictures had been painted at Iserda, Siwar, Jhillaya, Chommu, Malpura and Samod. The artistic activities of some centres of these feudal lords had emerged in the new style with many distinctive features.

At Uniara a new substyle developed, combining both Jaipur and Bundi styles. Frescoes of the palaces of Uniara and miniatures preserved in private collections of the Uniara royal family and Sangram Singh testify to this fact. Paintings in the palace of Samod were also drawn on the basis of the traditional frescoes of the Jaipur style.

Generally speaking, the traditions of frescoes available in palaces, temples and havelis had spread far and wide. The style of decorations which had adorned temples, cenotaphs and havelis in Shekhawati during the 19th century was influenced by frescoes of the Jaipur style.

Salient Features

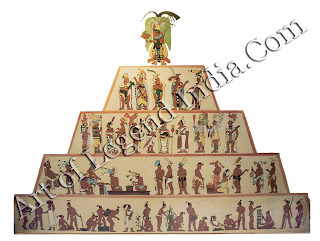

![The Month of Vaishakha The Month of Vaishakha]() The early Jaipur style being in accordance with the traditional Amber style and because of contacts with the Mughal court had flourished under the Mughal influence. But by and by it acquired the originality of Rajput culture, which had exhibited the predominance of the folk art character and grandeur of Rajputs in paintings of the Jaipur style.

The early Jaipur style being in accordance with the traditional Amber style and because of contacts with the Mughal court had flourished under the Mughal influence. But by and by it acquired the originality of Rajput culture, which had exhibited the predominance of the folk art character and grandeur of Rajputs in paintings of the Jaipur style.

The haveli of Pratap Narain, along with traditions of drawing frescoes in Galta, the haveli of Pundrik, Chandra Mahal, Sisodia Rani Palace and the palatial buildings of Nagar-Shreshthis and temples with hundreds of pictorial texts, thousands of miniatures and life-sized and larger portraits are specimens of the legacy of the Jaipur style.

According to Sangram Singh, the Jaipur style possesses the following significant features.

In the Jaipur style artists had infused a new tradition of painting life-sized portraits. Early pictures had certainly been drawn in a traditional style. Thou-sands of portraits and group paintings are salient features of the Jaipur style, in which portraits of feudal lords, artists and group paintings of royal processions, mehfils, utsav, colourful hunting scenes had been specially made. In the tradition of miniatures and pictorial texts, Geet-Govind, Ramayan, Krishna, Durga-Saptshati, Mahabharat, rag-ragini, barah-masa, nayika-bhed, the art of pleasure was extensively painted.

The fresco tradition is the main feature of the Jaipur style. In the Amber style, in palaces, temples, cenotaphs and havelis, arais was applied after the construction of Jaipur city and drawing of frescoes had become an integral part of architecture. This tradition gained great popularity in the 19th century and the seals of Shekha-wati built palatial new havelis in accordance with the new economic order in their respective towns and decorated them with a variety of paintings.

Artists in the Jaipur style applied deep reds in drawing margins on paintings. White, red, yellow were extensively utilised. Applications of gold and silver were also made.

In paintings of this style men and women appear in proportion. Male figures have clean, attractive faces. They are often depicted with swords tied to their waists. Regarding ornamented dress, males are shown wearing sehra tied with turra kalangi.

Wealthy men are shown wearing turban, kurta, pyjama, chogga, angrakin, belt, pataka, shoes in such paintings.

Female figures are shown with large eyes, bunch of long hair, stout physique and pleasant mood. Like other Rajasthani styles in this style too female figures adorned with tikka, toti, ball, necklace, hansli, satlan, tevta, kantha, banwanti, bangles, payajeb were depicted. In drawing dresses blouse, kurta, clupatta, lehnga, besor tilak and embroidered shoes were frequently used. Artists drew elegant gardens to provide the background in paintings. Lion, tiger, sheep, goat, camel, horse, ox, peacock, duck, parrot were painted to suit a picture's theme.

After 1950, because of the introduction of photography, coupled with foreign influences in art and architecture, foreign themes were introduced and assimilated in the Jaipur style, and the original characteristics of the style began to deteriorate slowly.

Uniara Substyle

![Baramasa series Baramasa series]() The wall-paintings of the palace of Uniara Thikana in Tonk district, the 'miniatures' from the personal collection of Rao Raja Rajendra Singh of Uniara and also the paintings from the personal collection of Kumar Sangram Singh, bear their own identity and these can be classified under Jaipur substyle. Situated on the border of Jaipur and Bundi States, Uniara Thikana imbibed the impact of Bundi

The wall-paintings of the palace of Uniara Thikana in Tonk district, the 'miniatures' from the personal collection of Rao Raja Rajendra Singh of Uniara and also the paintings from the personal collection of Kumar Sangram Singh, bear their own identity and these can be classified under Jaipur substyle. Situated on the border of Jaipur and Bundi States, Uniara Thikana imbibed the impact of Bundi

art due to matrimonial relations, and the influence of Jaipur art also on account of blood-relations thereby evolving a new style of painting which is known as Uniara substyle.

The descendants of Naruji of the Amber Kachhwahas came to be known as 'Naruka'. In his lineage Rao Chandra Bhan Dasawant (1586-1660) fighting for the Mughals displayed remarkable valour in the Kandhar Battle (1606). Pleased by his chivalry the Mughal emperor bestowed upon him the four parganas of Uniara, Nagar, Kakor and Banetha.

In the fifth generation of Rao Chandra Bhan was born an ardent art-lover Rao Raja Sardar Singh (1740-77) who built magnificent palaces in Uniara and Nagar, and patronised artists like Dheema, Meer Bagas, Kashi, Ram Lakhan and Bhim etc. A close observation of the wall-paintings of Nagar and Uniara palaces reveals the collective influence of Bundi and Jaipur substyles on them.

While Nagar wall-paintings show the total impact of Bundi style, Uniara paintings especially manifest the two-fold influence of Bundi and Jaipur styles. The wall-paintings of the ruined palace are greatly artistic, and these cover a variety of topics. Here we have paintings like Barahmasa based on Keshav's Kavi Priya, Ragragini, portraits of kings and a number of religious drawings. Among the portraits of kings, the personal portraits of Naruji, Dasaji, Chandra Bhan, Fateh Singh, Sangram Singh, Sardar Singh, Jaswant Singh, Bisan Singh, Bhim Singh, Budh Singh of Bundi, the kings of Jaipur, Kota, Mewar etc. have been painted with utmost excellence. Among the religious paintings, Krishna Leela, various incarnations, Shiva-Parvati are remarkably noteworthy.

The Uniara substyle is also revealed through the 'manuscripts' and miniature paintings. The Bhagwad Puran, Ramayan and a number of 'miniatures' from the personal collection of Rao Raja Rajendra Singh are very important from the point of view of art. In the personal collection of Kumar Sangram Singh lots of 'miniatures' are available among which the paintings of Zanani and Mardani Mehfil (Men and Ladies' Concerts) are worthy of special mention. Some paintings can also be sighted in the National Museum, New Delhi.

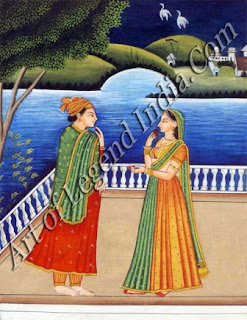

![Love in a Garden Love in a Garden]() On the basis of the achievements of above wall-paintings, 'manuscripts' and 'miniatures', the Uniara substyle has acquired a distinct form in which a new tradition of painting emerged from an amalgamation of two styles. The Uniara Thikana following the Kushwaha cultural tradition was under the domain of Jaipur state, and as such the Uniara substyle bears the stamp of total impact of Jaipur style in terms of structure, colour-scheme, and dresses etc.

On the basis of the achievements of above wall-paintings, 'manuscripts' and 'miniatures', the Uniara substyle has acquired a distinct form in which a new tradition of painting emerged from an amalgamation of two styles. The Uniara Thikana following the Kushwaha cultural tradition was under the domain of Jaipur state, and as such the Uniara substyle bears the stamp of total impact of Jaipur style in terms of structure, colour-scheme, and dresses etc.

A number of Jaipur painters have also contributed to this style. On account of the geographical proximity, located near Bundi as it is, and also due to the marriage of the daughter of Rao Raja Sardar Singh with Bundi King Dalel Singh, the Bundi painters had a chance to visit Uniara, and as such the total influence of Bundi style is marked on the architecture, natural-setting, face-structure and the decoration of these paintings.

In view of the Nagar and Uniara wall-paintings, there is a great scope for further work on this substyle.

Shekhawati Style

Studies of painting have also brought the Shekhawati region into the limelight. Traditional drawings of frescoes in the Amber and Bairath styles and paintings created in palaces, temples and particularly in the havelis of Jaipur influenced the Shekhawati region, and the haveli style of painting, music, architecture engulfed it.

In the 15th century Shekhaji, grandson of Mokulji, earned a great reputation for being a brave man, as great in the art of war as in imparting justice, who had set up an independent kingdom which acquired much fame as Shekhawati state. This territory is an integral part of the Rajasthan desert and is recognised as the confluence of wealth, education and art. Known as Marukan tar in the Ramayana and Mahabharata ages, this territory, engulfed within the boundaries of Matsya Pradesh, should be treated as lying within the campus of the Dhundar school.

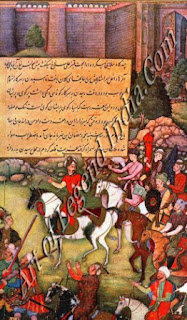

![A Raja in Procession A Raja in Procession]() In ancient days, this part of the land being surrounded by dangerous and dense forests and rich in deposits of copper was a great centre of culture. Recent archaeological excavations at Ganeshwar, ten kilometres from Neem-ka-Thana, revealed thousands of spikes of arrows, pointed edges of spears, ornaments, fish hooks and axes belonging to the copper age. A civilisation 5,000 years old has been discovered and proves beyond doubt that the copper used in the Harappan and Mohenjodaro and Indus Valley civilisations was procured only from this site. So old and abundant were these prehistoric utensils made of copper that they were not available else-where in the world."

In ancient days, this part of the land being surrounded by dangerous and dense forests and rich in deposits of copper was a great centre of culture. Recent archaeological excavations at Ganeshwar, ten kilometres from Neem-ka-Thana, revealed thousands of spikes of arrows, pointed edges of spears, ornaments, fish hooks and axes belonging to the copper age. A civilisation 5,000 years old has been discovered and proves beyond doubt that the copper used in the Harappan and Mohenjodaro and Indus Valley civilisations was procured only from this site. So old and abundant were these prehistoric utensils made of copper that they were not available else-where in the world."

The Ganeshwar civilisation would undoubtedly herald a new era in the annals of archaeology. Remnants of the Mahabharata and Ramayana and Bodh ages are sometimes discovered in Shekhawati. The influence of the art of Gurjara-l'ratiharas spread in wide areas of Shekhawati. Many spots like Jodhpura, Sunari, Harsh Nath, Shakambari remained as great centres of art and culture.

But the decline of painting in the Shekhawati region should be considered from the point of view of construction of havelis. After the establishment of British rule in Rajasthan capitalists of this area expanded their horizons of commercial activity. They entered into partnership with the British in trade and by dint of their initiative and unlimited boldness and with their jugs and ropes migrated to Bombay and Calcutta.

Shekhawati merged with various commercial centres in the early part of the 19th century and due to the exodus of traders to pursue their business activities else-where this territory became the cradle of the goddess Lakshmi. Hence the Birlas of Pilani, Poddars of Nawalgarh, Bangurs of Baggar, Ruias of Ramgarh and Dalmia, Bajaj, Jaipuria occupied significant positions in the Indian economy. They constructed large havelis, temples and cenotaphs in their towns and had them deco-rated by artists. The art galleries of haveis and their internal and external perspectives were adorned with attractive paintings.

As painting in havelis is a growth of the 19th century, it has been greatly influenced by folk art and the Company style. With the advent of the British, faster means of communication, new lifestyle, and development of new inventions, these wealthy traders painted their havelis on the British pattern. The cultural impact of the 19th century could well be studied in the Shekhawati style.

These havelis of seths laid out in vast areas were built on the principle of Bharatiya Shilpa-Shastra. Great scope exists to undertake the study of those located at Nawalgarh, Fatehpur, Laxmangarh, Mukundgarh, Churu, Sardar Sehar, Ramgarh from the point of view of artistic values and architectural principles. These were decorated with artistic wooden doors and gavaksh doors, and their front walls were adorned with paintings influenced by the Rajput and Company styles.

![Couple Embracing Couple Embracing]() Interiors of havelis were painted as far as possible. In some havelis art galleries were established with engraved mirrors and gold polish." Entrance gates were decorated artistically. In the above-mentioned towns paintings expressing the moods of Radha-Krishna are abundantly visible in temples. Cenotaphs located at Reengus, Ramgarh, Bissau, Choori Ajitgarh were elaborately painted in an advanced stage of the Amber style.

Interiors of havelis were painted as far as possible. In some havelis art galleries were established with engraved mirrors and gold polish." Entrance gates were decorated artistically. In the above-mentioned towns paintings expressing the moods of Radha-Krishna are abundantly visible in temples. Cenotaphs located at Reengus, Ramgarh, Bissau, Choori Ajitgarh were elaborately painted in an advanced stage of the Amber style.

There is not a single town in Shekhawati where havelis and temples have not been decorated with paintings. From the point of view of impact of painting, Shekhawati may be classified in three parts:

1. Region adjoining Jaipur: frescoes at Chommu, Samod, Reengus. Srimadhopur, Ajitgarh are greatly influenced by the Jaipur style. Their themes and colouring tend to be very close to that style.

2. Styles of paintings at Patan, Ganeshwar, Chhapoli, Khetri and many towns of Jhunjhunu were greatly influenced by the folk art of Haryana.

3. Effect of the Marwar school was very great at Nagore, towards Bikaner and towns located in the western part of Sikar. But even after this traditional impact the Shekhawati style appears to maintain its own characteristics.

Salient Features

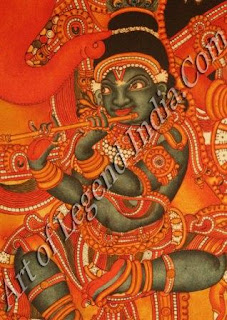

![Sri Krishna with the flute Sri Krishna with the flute]() 1. Drawings of elephants and horses and guards were made in bold relief in the brackets of havelis.

1. Drawings of elephants and horses and guards were made in bold relief in the brackets of havelis.

2. Drawings of gods and goddesses were painted in sharp outlines on gavaksh and main gates.

3. Below projections, in spaces between todas artists skilfully painted themes like wrestling, churning, godohan, dhola-maru, nayika engaged in shringar, curious animals, birds, divine manifestations, demons, kant-kala, love, rag-ragini, barah-masa, saints and ascetics, folklore.

4. The exterior and interior walls of many havelis are covered with pictures showing the impact of the Company style and of industrialisation. Railway trains, motor vehicles, bicycles, sewing machines, aeroplanes, sofa sets and other articles belonging to the Victorian age may be seen. The impact of British rule brought great changes in manner of eating, style of dressing, way of living, which have been well depicted in these paintings.

Areas of Shekhawati like Sahapura, Ajitgarh, Patan, Khetri, Bissau, Pilani, Chirawa, Nawalgarh, Ramgarh, Baggar, Sikar, Reengus, Chommu, Samod, too could prove useful within limits for a special study of artistic growth.

Alwar Style

![The gracious manifestation of devi The gracious manifestation of devi]() As a study of the Alwar style has never been undertaken, it has not come into the limelight. Occasional references have however been made to it by connoisseurs of art from time to time. In regard to painting, examination of available materials (frescoes), manuscripts, miniatures, plates of ivory, mica and wood reveal a style of painting no less impressive than other styles of Rajasthan.' Examples of this style are preserved in many museums, temples, palaces and in private collections yet to be researched.

As a study of the Alwar style has never been undertaken, it has not come into the limelight. Occasional references have however been made to it by connoisseurs of art from time to time. In regard to painting, examination of available materials (frescoes), manuscripts, miniatures, plates of ivory, mica and wood reveal a style of painting no less impressive than other styles of Rajasthan.' Examples of this style are preserved in many museums, temples, palaces and in private collections yet to be researched.

Like other styles, the origin of this style is presumed to have taken place after the establishment of Alwar state. Rao Raja Pratap Singh (1756-1790), by his bravery, intelligent statesmanship and political ability created an independent kingdom after conquering parts of Bharatpur and Jaipur.' In 1770, after having laid out Rajgarh on a new pattern, he constructed a strong fortress there and made it his capital. About this time two artists named Dhalu Ram and Shiv Kumar migrated to Alwar from Jaipur." They presented some of their artistic work to the maharaja. Shiv Kumar is believed to have-returned to Jaipur but Dhalu Ram was appointed in charge of the state museum, which contained the private collection of pictures of the royal family.

![Ragini Gauri Ragini Gauri]() Dhalu Ram was skilled in drawing frescoes. The beautiful frescoes in the Sheesh Mahal of Rajgarh fort were probably painted under his supervision. If we admit this view, these frescoes may be presumed to be the best specimens of the early stage of the Alvvar style.

Dhalu Ram was skilled in drawing frescoes. The beautiful frescoes in the Sheesh Mahal of Rajgarh fort were probably painted under his supervision. If we admit this view, these frescoes may be presumed to be the best specimens of the early stage of the Alvvar style.

About 30 kilometres from Alwar at Rajgarh, a beautiful palace of glass is located on the upper portion of the fortress. Paintings on perforated screens and lower walls deserve high praise. This Sheesh Mahal is located in two parts, a big hall about 25 feet by 12 feet and a verandah 25 feet by ten feet adjoining it from the north.

The ceiling of the hall is studded with glass of different colours, and white glass is engraved on the walls. At occasional spaces, many paintings were executed while the walls below the perforated screens are decorated with the foliage of trees.

The frescoes of this palace show a variety of themes, including paintings relating to Krishna-Chant, Ram-Chant, nayikas, the royal court, music which may be presumed to be early developments of the Alwar style. Paintings concerned Ram Lila, Goverdhan Dharan, Gocha ran, Hindola, Veni-gunthan, churning of milk and Ram's valour.

Raj Tilak and other artists are concerned with Krishna and Ram Lila. Among them, drawings of cows and seven coloured drawings deserve close attention. The drawings of Dhanush Bhang and Raj Tilak possess large dimensions, and elephant and horse riding revive memories of Ajanta.

![Krishna Lifted Goverdhan Mountain Krishna Lifted Goverdhan Mountain]() Drawings of yawning nayikas removing a thorn, nayikas and maidservants engaged in beautification, are very pleasant. Paintings of women playing the tabla, sitar and sarangi are less pleasing. Scenes of the royal courts of Maharaja Pratap Singh and Bhaktawar Singh are painted on the walls. Blending of colours in various designs of foliage and the rhythm of the drawings are very impressive. Lines are very sharp and bold in relief.

Drawings of yawning nayikas removing a thorn, nayikas and maidservants engaged in beautification, are very pleasant. Paintings of women playing the tabla, sitar and sarangi are less pleasing. Scenes of the royal courts of Maharaja Pratap Singh and Bhaktawar Singh are painted on the walls. Blending of colours in various designs of foliage and the rhythm of the drawings are very impressive. Lines are very sharp and bold in relief.

The whole job was probably executed by an artist of great merit like Dhalu Ram. In the Sheesh Mahal of Rajgarh fort, the effect of the almond colour of the Ajanta style is very evident. Light green, blue and gold used in these paintings are impressive.

Sheesh Mahal was constructed around the period of Rao Raja Bhaktawar Singh (1790-1814) son of Rao Raja Pratap Singh. Bhaktawar Singh himself was a poet and keen lover of poetry. It is a sad reality that most of these paintings have started to deteriorate in the absence of patronage.

Bhaktawar Singh composed poetry under the names Chandra-Sakhi and Bhaktesh. Dan Lila is a very significant text he compiled. Having heard praise of Rao Raja's patronage of the arts, many artists from distant states came to Alwar, where their talents were suitably rewarded. In their period Alwar flourished culturally. Baldev Salga and Salig Ram were leading artists of the state.

Hundreds of paintings belonging to the time of Bhaktawar Singh are preserved in the State Museum, Alwar, which are worth seeing. Among them are pictures depicting the maharaja himself engrossed in religious conversation with naths and jogis, ascetics living in dense forests. They deserve special appreciation from the artistic point of view. Most of the paintings preserved in the museum belong to Bhaktawar Singh.

After Rao Raja Bhaktawar Singh, for having given a new direction to the Alwar style the credit goes to his successors Maharaja Vinay Singh (1814-1857) and Raja Balwant Singh (1826-1845) of Tijara. In their period the style reached its zenith.

Vinay Singh earned a big reputation among kings of Alwar for his keen love of art. He contributed towards the development of the Alwar style as much as Akbar did for the Mughal school.

Hearing he was a connoisseur of art and virtuous, many artists, architects, scientists and musicians thronged to his court to emulate his example. It was in this period of Bahadur Shah (1806-1837) and Bahadur Shah III (1837-1859) that the Mughal Empire with its capital Delhi began to shrink in size and disintegrate politically.

![Woman bathing Woman bathing]() Maharajas Vinay Singh and Balwant Singh were great connoisseurs of art and enriched their museum after purchasing artistic items. They organised a big library after procuring many pictorial texts. Rare games and unique arms were procured to enrich their collections of jewellery and armouries, and having provided royal patronage to artists they gave a dynamic thrust to the art of painting. They had a golden opportunity to display their artistic talents in the reign of Vinay Singh. He had learnt this art from Baldev, who occupied a high position at the royal court. He had originally worked in the traditional Alwar style. Later, he produced beautiful paintings strongly influenced by the Mughal school.

Maharajas Vinay Singh and Balwant Singh were great connoisseurs of art and enriched their museum after purchasing artistic items. They organised a big library after procuring many pictorial texts. Rare games and unique arms were procured to enrich their collections of jewellery and armouries, and having provided royal patronage to artists they gave a dynamic thrust to the art of painting. They had a golden opportunity to display their artistic talents in the reign of Vinay Singh. He had learnt this art from Baldev, who occupied a high position at the royal court. He had originally worked in the traditional Alwar style. Later, he produced beautiful paintings strongly influenced by the Mughal school.

Maharaja Vinay Singh was keenly interested in getting pictorial texts painted as well as scrolls of script paintings. Because of this he invited Gulamali, a seasoned artist, Aga Mirza of Delhi, a great calligrapher, and Nathha Shah Dervesh, a highly skilled bookbinder also of Delhi. Calligraphy and painting texts like the Ramayan, Mahabharat, Srimad Bhagwad Gita, Geet-Govind, Durga-Saptashati, Gulistan, Koran unmistakably reflect the keen devotion of Vinay Singh to artistic activities. Calligraphy and drawing of Gulistan were a unique feature of his reign. Creation of this text cost Rs. 1 lakh. Pictures of the text were drawn by Baldev and Gulamali. All the calligraphy of this work was formed with a pen made of sect ha. If a mistake appeared on any page the whole page was done all over again.

Many sets of paintings of rag-ragini in the Alwar style are still available. Most of them had been painted during his period. A set of barah masa based upon verses of an unknown poet Anand Ram belongs to this time.

Khawaswal queen, Moosi Maharani of Rao Raja Bhaktawar Singh had per-formed the rite of Satti alongwith Rao Raja having left her son. Her son Balwant Singh had created trouble to secure the throne himself. To avert armed conflict the northern part of the state was handed over to Balwant Singh in 1826. He had made Tijara his capital but died without issue in 1845. Tijara was thus merged with Alwar state again.

In his reign of 23 years he devoted himself to the pursuit of artistic values, and his great contribution in this regard is a memorable event in India's cultural history. He was a king keenly devoted to promoting the arts. At his royal court artists like Salig Ram, Jamuna Dass, Chhote La!, Baksa Ram and Nand Ram had painted pictorial texts, scrolls and miniatures extensively. Paintings by Jamuna Dass up to 1844 are available, and the names of Raja Balwant Singh and the artists who worked on these pieces are inscribed on them.

![Procession at hawa mahal Procession at hawa mahal]() The paintings of Jamuna Dass, with their bold relief in line and soft, tender colour schemes are worth seeing. Paintings with the name of Baksa Ram belonging to this period are preserved in the state museums and in private collections of Maharajkumar Yashwant Singh of Alwar's family.

The paintings of Jamuna Dass, with their bold relief in line and soft, tender colour schemes are worth seeing. Paintings with the name of Baksa Ram belonging to this period are preserved in the state museums and in private collections of Maharajkumar Yashwant Singh of Alwar's family.

After the merger of Tijara, the artistic heritage and artists moved to Alwar. Vinay Singh and Balwant Singh enriched their museum there after buying works of art from the royal treasury and library of the Mughals. Historic pictures of Mughal emperors, books, a Shahi album, sets of miniatures, weapons, dresses and equipment studded with precious stones are regarded as the proud heritage of the museum which would shed new light on the history of the Mughals.

![A rajputana procession A rajputana procession]() Diwanji ka Rang Mahal, built in the reign of Vinay Singh (1830) deserves careful study for its frescoes. In the tradition of frescoes in the Alwar style it is another significant specimen. The forefathers of Bal Mukund held the position of diwan of Alwar state from time to time and Bal Mukund (1783-1855) held it under Maharaja Bhaktawar Singh. He had also served as diwan to Vinay Singh. Brave and benevolent, he was also highly religious and a keen lover of art.

Diwanji ka Rang Mahal, built in the reign of Vinay Singh (1830) deserves careful study for its frescoes. In the tradition of frescoes in the Alwar style it is another significant specimen. The forefathers of Bal Mukund held the position of diwan of Alwar state from time to time and Bal Mukund (1783-1855) held it under Maharaja Bhaktawar Singh. He had also served as diwan to Vinay Singh. Brave and benevolent, he was also highly religious and a keen lover of art.

A manuscript was compiled by his grandson about the haveli and Sheesh Mahal around 1836-37. Diwan Bal Mukund had the havell constructed at the well of Munshi Bagh for his residential purposes. Very large, it is also sturdily built. Its gate is located in the west. A passage near this door leads to the Sheesh Mahal situated on the upper portion, in which gold workmanship of high quality and engraving of mirrors in various patterns and in different shades of colours had been performed.

![Holi Festival Holi Festival]() This Sheesh Mahal was also constructed on the same plan as that of Rajgarh. A big room and a verandah in a northerly direction deserve admiration for architectural beauty. The walls of the room are studded with chips of white glass with paintings on a rectangular panel between the ceiling and the wall decorated with paintings depicting 24 incarnations, their six rag-raginis and various musical modes.

This Sheesh Mahal was also constructed on the same plan as that of Rajgarh. A big room and a verandah in a northerly direction deserve admiration for architectural beauty. The walls of the room are studded with chips of white glass with paintings on a rectangular panel between the ceiling and the wall decorated with paintings depicting 24 incarnations, their six rag-raginis and various musical modes.

On the wall, attractive murals depicting Goverdhan-Dharan, Veni-Gunthan,, Hindola, Raj Tilak and mehfil have been painted. Paintings of nayikas and doorkeepers are also very pleasant to look at. From the point of recalling a sentimental experience the frescoes of the Alwar style are unique. Well preserved, their condition is better than those of Rajgarh, but on the whole the lines of this Rang Mahal and the application of colours do not display the kind of charm noticeable in the Sheesh Mahal of Rajgarh.

This Rang Mahal, built in the period of Vinay Singh (1814-1857) amid the old havelis of Alwar, still reminds of the glories of old. The construction of many temples and palaces and the workmanship of foliages in various shades of colour make us understand the Alwar style.

The Sheesh Mahal of the Raj Mahal at Alwar is in a dilapidated state. Built in the last days of Vinay Singh, in the midst of mahal paintings of Shiv-Parvati and Ganesh drawn in a big room, they do not pay such attention to detail.

These paintings depict clearly the impact of photography. In the adjoining room, miniatures painted on paper were pasted on the wall and covered with glass, but such types of frescoes could not be regarded as belonging to the traditions of fresco painting though such experiments could be noticed in many other palaces of Rajasthan.

After Vinay Singh the period of Sawai Shiv Dan Singh is no less significant from the point of view of painting. He was learned in Persian and Hindi and had a special love for painting and music. His artistic tastes were well suited to his luxury-loving temperament. Hundreds of erotic paintings based upon Kam-kala and drawn in his time are good artistically.

Being very fond of music, his court was crowded with saniras and dancing girls. Hundreds of such paintings depicting these gayikas are still available in private collections of the royal family, which show the effect of the Company's style besides that of photography.

In his time, an era of deterioration began in the Alwar style. With the Western impact the photograph began to receive greater prominence and the poetical beauty, sharpness of colour and bold relief in line and drawings of purdahs began to lose ground slowly.

Maharaja Mangal Singh, unlike his ancestors, had no love for the line Budha Ram, Udai Ram, Moo! Chand, Jagan Nath, Ram Gopal, Bishen Lal continued to maintain in the Alwar tradition of painting.

![Nafeeri Vadan Nafeeri Vadan]() Budha Ram had mastered the art of drawing animals and birds. He held the position of daroga of the Sheesh Mahal of Rajgarh and the museum of Alwar. Mool Chand acquired expertise in painting ivory pieces. Many paintings drawn on pieces of ivory are a unique feature of the Alwar style.

Budha Ram had mastered the art of drawing animals and birds. He held the position of daroga of the Sheesh Mahal of Rajgarh and the museum of Alwar. Mool Chand acquired expertise in painting ivory pieces. Many paintings drawn on pieces of ivory are a unique feature of the Alwar style.

The traditions of painting frescoes also flourished in temples and cenotaphs in Rajasthan. Alwar had not lagged behind in the art of frescoes. In temples built by the mother of Mangal Singh at Thana and Bhurassidih many paintings had been executed. But these paintings being of later dates are not so artistic. In the temples of Raj Mahal some scattered paintings are still available although they almost vanished in the absence of official protection. In the temple of Lacidu Khavasji glass was fixed over paintings made on paper on walls.

The frescoes drawn on cenotaphs belonging to Hanuvant Singh of Thana, Khavasji-ka-Bagh of Rajgarh, and the garden of Macchedi and on Tal Briksh, although time-worn exhibit glimpses of grandeur even today. Among them, a large number of paintings depicting the lilas of Ram and Krishna and scenes of the royal court and state processions were drawn. Certainly, the art of these cenotaphs had greatly influenced folk art. The effect of folk art is more pronounced in the arrangement of lines and choice of colours.

Examination of the frescoes of the Alwar style shows that the style of painting developed there had flowed in dual waves, one in engraving frescoes, and the other into pictorial texts and miniatures.

In the reign of Jai Singh, former Maharaja of Alwar, architecture, music and painting flourished. A large portrait of his shows a scene of one of his processions and deserves special mention. Ram Shaya Nepalia, who painted this picture, should be remembered. In the history of Rajasthani art, the contribution of artistslike Ram Gopal, Ram Prasad, Jag Mohan and Onkar Nath is no less significant.

Subject

![A Beautiful Lady A Beautiful Lady]() As remarked earlier, the Alwar style attained diversity in regard to theme. In the royal courts of Rajputs,. mehfils, Krishna-Lila, Ram Lila, religious conversation with saints and ascetics in natural surroundings, rag-raginis had been extensively painted. Vinay Singh and Balwant Singh had specially got them painted like rag-ragini, barah-masa and pictorial texts in Hindi and Sanskrit which included the Mahabharat, Geeta, Ramayan, Shiv Kavacch, Durga-Saptashati, Geet-Govind, Kali Sahasra-Nama and Mahiman Stotra. Because of the contact with Muslim artists and feudal lords from the Mughal court, the Alwar style of painting was more influenced by the Mughal school and its themes in place of Rajput grandeur.

As remarked earlier, the Alwar style attained diversity in regard to theme. In the royal courts of Rajputs,. mehfils, Krishna-Lila, Ram Lila, religious conversation with saints and ascetics in natural surroundings, rag-raginis had been extensively painted. Vinay Singh and Balwant Singh had specially got them painted like rag-ragini, barah-masa and pictorial texts in Hindi and Sanskrit which included the Mahabharat, Geeta, Ramayan, Shiv Kavacch, Durga-Saptashati, Geet-Govind, Kali Sahasra-Nama and Mahiman Stotra. Because of the contact with Muslim artists and feudal lords from the Mughal court, the Alwar style of painting was more influenced by the Mughal school and its themes in place of Rajput grandeur.

According to the selection of themes the third phase began from the time of Maharaja Shiv Dan Singh (1857). Because of the impact of photography portraits of individuals were made in large numbers. Hundreds of paintings concerning Ganikas and Kam-Shastra are still available. Yogasan was also treated as an important theme of the Alwar style. In this way the tendency towards painting individuals increased against drawing groups.

Salient Features

![Nafeeri Vadan Nafeeri Vadan]() In early paintings, till the period of Bhaktawar Singh, all the salient features of Rajasthani painting are clearly noted in the Alwar style. Hence it becomes rather difficult to dissociate them from the Jaipur style. But still the effect of natural beauty, the way of living and physical characteristics of the state are clearly discernible in such paintings. These paintings, endowed with lyrical sentiment and folk art, appeal in line and colour.

In early paintings, till the period of Bhaktawar Singh, all the salient features of Rajasthani painting are clearly noted in the Alwar style. Hence it becomes rather difficult to dissociate them from the Jaipur style. But still the effect of natural beauty, the way of living and physical characteristics of the state are clearly discernible in such paintings. These paintings, endowed with lyrical sentiment and folk art, appeal in line and colour.

In its most significant days a balanced coordination of the Rajasthani (particularly Jaipur) style and Mughal and Persian schools is clearly visible. Because of this coordination a separate identity could be given to the Alwar style. Figures of males were drawn like the mango or some curve was provided to the chin. Their stature is slightly short with raised bons, their limbs were drawn with great pains, and these represent salient features of the Alwar style.

The local effect is seen in the tie-and-dye work of the turbans. The impact of Rajput and Mughal styles upon the dress of male and female is largely evident. The natural perspective of Alwar may be viewed in paintings of this style with drawings of forests, gardens, kunj, palaces and so on.

Construction of beautiful vaslian adorned with attractive foliage is a remarkable characteristic of the Alwar style. Trade in these vaslis continued to flourish till 1947. Merchants bought vaslis designed with foliage from there and covered them with old paintings, and thus greatly enhanced their beauty. Application of bright colours made these paintings very attractive, especially with the use of red, green and gold. Drawings of white clouds, clear sky, forests and gardens full of animals and birds, rivers, mountains were painted according to the natural perspective of Alwar.

Writer – Jai Singh Neeraj